Engineer's Bench: Farming for Old Tech

Six vacuum tube voltmeters that had been stored in a milk crate provided a challenging restoration.

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I’m always looking for that “barn find” when searching for vintage equipment. I hit the mother lode when I found a milk crate filled with vintage vacuum tube volt meters (VTVMs), six sets of probes/leads, and a book from 1967 on tubes at a silent auction. I had no idea if any of the meters worked or any idea where to house them if I won. With only one bid of $20, I took a gamble and bid $25.

[MORE FROM GLOMAN: Restoring the Spirit of Radio]

Winning the milk crate and its contents, I rushed home with my new treasures. The contents included a Philco 6110, Eico 221, RCA WV77A, Heathkit 77A, RCA Model V-7A, and Arkay 012, as well as an Approved Electronic Instrument Company A1 volt-ohm milliammeter (VOM). My first step was to look for schematics on each of these models. With those in hand, I would take each one apart and determine what needed to be done.

More Than History

You may be wondering why, in this day and age, restoring vintage tube testing equipment would have any purpose. Besides the fun factor of getting something old that's not working to function again, this old technology actually is still useful today.

When you're using a voltmeter in the digital world, the numbers are scrolling across the screen very quickly, which sometimes makes it difficult to get an accurate reading. In the analog world, you're looking at a meter. Sometimes it's more efficient to see a needle at a specific number than trying to stop digital numbers that are flying by at a rapid rate.

Some people may find it hard to believe, but another reason is that at times, an analog meter is actually better to use than a modern digital meter because of the voltage. If you're measuring something with extremely high voltage, like most tube equipment, you could easily destroy a modern meter if you have it at the wrong setting. Older analog meters were designed just for this purpose and can better handle higher voltages.

Another reason is when you're looking to test the value of a specific component, the numbers (at least to me) are more difficult to comprehend on a digital scale. If you're seeing that same scale on an analog meter, if the dial is pointed 1/3 of the way up the scale, you know that particular component is 1/3 of its actual value. The math is simple.

A daily selection of the top stories for AV integrators, resellers and consultants. Sign up below.

And the fourth reason: When you're restoring a piece of vintage electronics, using vintage test equipment in the process just seems like the right thing to do. I'll let you in on a little secret: I use both digital and analog for a variety of things. Digital may be more modern, but sometimes that's not the way you want to go.

Defining Differences

So, what’s the difference between a VOM, which I had one, and a VTVM, which I had six? General Radio introduced the first VTVM, with an input resistance in the order of 10 megohms, while the VOM had a relatively low input resistance, limited ranges, and were much smaller. This made it less useful as circuit impedances increased and the levels of measurement for voltages and resistances decreased. Essentially, this relegated VOMs to appliance servicing, where exact measurements weren’t necessary.

The VTVM differs from the VOM in that the meter is driven by a vacuum tube circuit. In this way, a very high input impedance (11 megohms is typical) is obtained on almost all ranges, resulting in negligible circuit loading. Since the tube circuit acts as a buffer between the meter and the circuit being tested, the VTVM has a built-in meter protector. And since the tube circuit has gain, a more sensitive measuring instrument can be designed.

A very simple description as a takeaway for VTVMs: Most use similar circuitry where a pair of triode tubes amplify the DC voltage coming in through the probe and a range voltage divider to drive the meter. One advantage of the VTVM is that the tube circuit can be tailored to have a wide frequency response. The biggest advantage is when you’re working on semiconductor circuits, but that’s a whole other article.

Starting Off Simple

I began my restoration efforts with the RCA WV77A Junior Voltohmyst Meter. It was simple looking, had just one input, and looked like a starter piece of test equipment that you would use on your bench—with the telltale paint spots. Why were people always painting back in the “old days,” and why did they always spill paint on their equipment?

Any piece of vintage tube equipment can benefit from a filament test. This involves putting a digital voltmeter (DVM) probe in each side of the AC plug, setting the meter to Ohms, and turning on the vintage unit. If numbers appear on the DVM, the tubes are working. All tubes must be present for this test to work.

Of course, if this is a DC-powered meter, the filament test doesn’t apply. Because the AC cord had some stress issues, I replaced it before I did any further testing. Opening the back revealed that the “D” battery was in bad shape, the bottom portion had yellowed, and the wax capacitors would need to be replaced.

Normally, a battery provides a stable DC voltage for ohms operation because its voltage is set by its chemical composition for a given current drain. This drain on the battery is miniscule; it’s meant to last and maintain an accurate voltage for a long time. The problem with restoring meters like this is that the battery may have been forgotten and it continues to drain, plus the corrosive chemicals begin to leak internally and may do damage.

Something to remember when cleaning VTVMs: Experts say not to use a lubricant like WD-40 to “grease” or clean rotary switches. It can cause a small current leak path that will make your meter operate erratically, and its residue hard to remove.

When checking resistors, usually one end needs to be removed from the circuit for an accurate test. And there’s a whole bunch of resistors in VTVMs! Some resistors, especially those in the input divider circuit, which is mounted on the rotary range switch and may be lined up on the main circuit board, have a 1% tolerance. Your meter readings will not be accurate if these are out of tolerance. You could recalibrate the meter to adjust for this, but then everything else would be off—a slippery slope.

Each tube was tested along with the resistors. I assumed the resistors would probably still be within range. The RCA WV77A was neat and tidy inside, and it was simple to upgrade and restore. One down, six to go.

Grease and Leaky Batteries

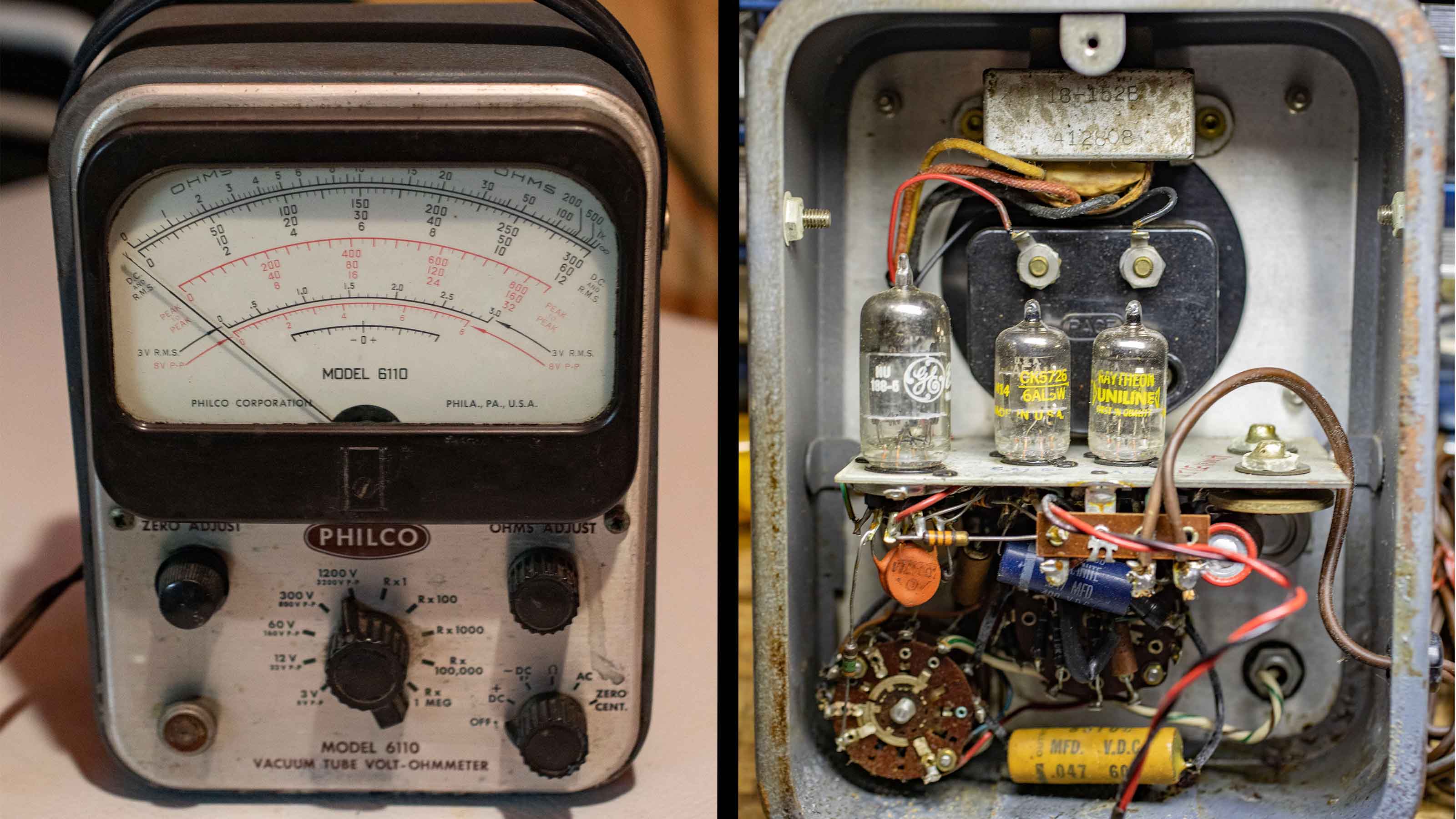

Next up was the Philco 6110. The only documentation I could find on this VTVM was a vintage ad. The main thing that made this unit memorable was that it left a trail of grease on my hands, workbench, and everything else from the first time I picked it up. It was a mechanic's tool when repairing radios, but I think a grease gun was too handy and leaked all over it. My nickname for it: Pigpen.

I wore disposable gloves throughout the restoration, even after I cleaned the exterior. The interior was like the previous meter, three tubes and three wax caps. The .047mf wax capacitor was burnt, and the others needed to be replaced because of age. The new capacitors were replaced.

Not taller than a pen, the winner of the cutest meter contest was the Approved Electronic Instrument Company’s A1 VOM. Since this was probably a kit, and so many companies existed that had test equipment in kit form, I couldn’t find any documentation or advertisements.

With the back removed, I discovered what I would see in every meter’s interior—leaking batteries. This issue needed to be addressed. If I put new batteries inside, they too would eventually leak. The best solution was to replace the batteries with an AC power supply. Finding a 5-volt AC/DC wall wart in a thrift store for one dollar, I cut off the female adapter end, attached the VOM’s battery’s wires to each lead of the adapter, and soldered and heat shrunk the cables. The wire exited the unit safely through a hole I drilled in the back of the metal case.

The meter was up and running with new caps, a cleaning of the exterior, and AC power. This was definitely my favorite of the bunch and has a prominent place on my bookshelf.

The RCA V-7A was the next meter to arrive at the workbench. Like the other meters, it had its share of dirty knobs that could be easily cleaned by soaking them in Dawn Detergent and water. The scale adjustment ranges are typical of VTVMs from this era.

Opening the back revealed a vintage Eveready C battery and an electrolytic capacitor. I figured the non-leaking battery was long dead, but it tested at a surprisingly good 1.48 volts. This is the only meter out of the batch that didn’t contain a leaking battery. I removed the battery to get at the wax capacitor inside.

The electrolytic capacitor was easily accessible on the circuit board. Whoever had assembled this kit was very neat. Testing the capacitor was the best way to solidify my belief that its value was no longer within range. Reading what should be a micro farad (mf) capacitor as a pico farad (pf) is a clear sign that replacement was necessary. Replacing it with a 15mf radial capacitor saved real estate and got the meter back within operating range.

To ensure that the meter was restored to operating condition, the resistors also needed to be tested. Each of these resistors would have one lead removed to get an accurate resistance reading. This was another reason to appreciate the neat job of the original builder. The meter would be calibrated after its plastic meter surface was cleaned.

The Basket Case

With its golden borders and styling, the Arkay 012 VTVM looked like something out of a 1930s horror movie. Also built from a kit, the large red bulb let you know when the meter was turned on. The repair/refurbish of the Arkay was the easiest. It just needed new caps. The next red-light unit was the Eico 221 VTVM. One screw was missing on the front, all the wax caps were replaced, and the exterior cleaned up.

Last up was lucky number seven—what I called the basket case. This 1946 Simpson 215 VTVM was probably the most well-known meter of the dirty seven, costing an expensive $32.50 in 1946, and had four inputs for leads on front, more than the others. However, it was unloved, had no screws, and was dead. Once I opened it, I saw why it was unloved: Someone was working on it at one time and apparently gave up!

Pulling apart the case revealed the corroded and yellowed AA batteries. Plus, the capacitors were wrapped in something which would take time to extricate. The heavy rust on the nut behind the round dial indicated this Simpson was a swimmer.

The back was the worst. For the best known of the collection of seven, the inside had been worked on and were pulled apart (and not too neatly). The resistors were soldered haphazardly, wires were disconnected, and the usual wax caps needed to be replaced.

This VTVM alone was worth paying $25 for the lot. It was the proverbial “barn find.” I’ve always wanted a vintage Simpson, but I had expected to pay much more (and had hoped for one in better shape). Current values on eBay range from $40 for a “for parts” 215, up to $172 for a restored model. Simpsons were what people used in the day.

I spent several weeks cleaning up this vintage Simpson. The fact that the wires in my Simpson were bundled was good, but the three wires that moved from their connections would have to be pulled from that bundle, which is bad. It was a challenge, but armed with the schematic and the owner’s manual, I was able to get the unit up and working.

Chuck Gloman, Associate Professor, has more than 40 years of experience as a producer and director of photography with more than 900 TV commercials, 250 corporate videos, and 100 documentaries to his credit. His films have aired on HBO, Cinemax, and network television. He is the author of Placing Shadows: The Art of Video Lighting, 2nd Edition (Focal Press: 2000); No Budget Digital Filmmaking (McGraw-Hill: 2002); 303 Digital Filmmaking Solutions (McGraw-Hill: 2002); 202 Digital Photography Solutions (McGraw-Hill: 2003); Placing Shadows: The Art of Video Lighting, 3rd Edition (Focal Press: 2005); Scenic Design and Lighting Techniques (Focal Press: 2006); Working with HDV (Focal Press: 2006); Placing Shadows: The Art of Video Lighting, 3rd Edition (translated in Japanese Language Focal Press: 2007); and Placing Shadows: The Art of Video Lighting, 3rd Edition (translated in Chinese Language Focal Press: 2017). He has published more than 500 articles.