Opryland Hotel and Convention Center Embraces Peavey MediaMatrix

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

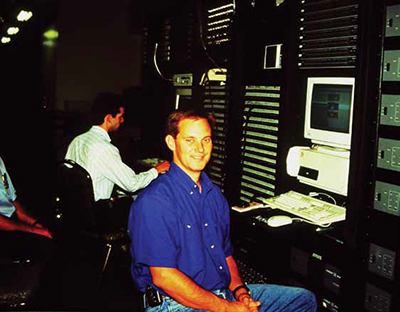

Vance Breshears was part of the team that implemented one of the first computer-based audio processing and routing systems

at the Opryland Hotel and Convention Center.There are certain projects that stand out, and for Vance Breshears, the Opryland Hotel and Convention Center was one of them.

Nashville is not just any town, and as such, Opryland is not just any meeting place. And so, back in the mid-’90s when Gaylord Entertainment Group, the hotel’s management, embarked on the fourth phase of an expansion project, it mandated technology that was, well, not just any technology. As part of this phase, the hotel— which at the time comprised 4,000 rooms and one million square feet of conference and exhibit space—was constructing a large, 900-seat ballroom that could be divided into four smaller spaces, as well as a four-and-ahalf- acre glass-enclosed atrium called The Delta. Breshears, then in the early years of his relationship with the Dallas-based design firm Acoustic Dimensions (where he is now a director), along with his colleague Craig Janssen (the firm’s managing director) was charged with designing a technical system that delivered computer-based audio processing and control, and that was easy to operate by a single person, or via wall-mounted, remote control interface panels.

Enter Peavey MediaMatrix, which was in the process of revolutionizing computerbased audio processing and routing. “These systems were really the first of a new generation of systems that could do a lot of different things,” Breshears said. “MediaMatrix could be operated in all of the rooms in any kind of configuration.” The firm also specified Crest CKS and CKV Series computer-controlled amplifiers. “We wanted to be able to do impedance sweeps of the amplifiers to make sure that they were working correctly. Because we had the ability to do impedance sweeps, it was actually pretty easy to troubleshoot some of the installation problems that cropped up. We didn’t have to bring in a bunch of extra test equipment—it was right there as part of the system and we could troubleshoot things rapidly and solve a lot of the problems.” A Crestron control system was specified to manage the MediaMatrix systems and enable the adjustment of input and output levels in each of the spaces.

What made this project so special was the level of flexibility the technology offered. “It was the first completely open architecture DSP system you could get into and program, and make the system whatever you wanted it to be,” Breshears said. “You weren’t limited by specific hardware boxes; you were able to use software-based modules inside of MediaMatrix that would represent hardware boxes.” The system, he added, could be anything you wanted it to be.

“The MediaMatrix was really the result of the hotel leadership’s desire for very comprehensive control systems,” Janssen said. “Prior to that time, we really had discrete systems control, so each element of a system, each space—be it a ballroom or a restaurant, or so forth—was either via individual systems control, space by space, or it would be an analog integrated system.” This was complicated when it came to both set-up and control, he added, and was often inflexible and inconsistent. “The promise of going completely digital was very exciting.”

Robert Rose, now vice president at Acoustic Dimensions, was project engineer for Ford Audio-Video Systems—the Oklahoma Citybased systems contracting firm charged with integrating the system—at the time. He noted that it was his first experience with a DSP system that, as he put it, appeared to have very few restrictions. “You needed to get all the inputs and outputs wired, but after that it was all software programming,” he relayed. “There were very few limitations, and infinite possibilities.” He added that this is not to minimize the degree of physical installation it required—which involved hundreds of inputs and outputs—but he says that software programming took center stage. “This has now become more of the norm, but remember up until that point you had to use a large number of analog or basic fixed digital devices and had to completely map out all of the routing and functional options.”

For Breshears, it was for this reason and others that Opryland remains a memorable project. “It was a risky project, and we were doing something new and different,” he said. “And because of that, you run the risk of having some challenges and some growing pains. We certainly had that with this project. But it’s one of those that sets a precedent for future projects. It definitely did that for us.”

A daily selection of the top stories for AV integrators, resellers and consultants. Sign up below.

Carolyn Heinze is a freelance writer/editor.

Carolyn Heinze has covered everything from AV/IT and business to cowboys and cowgirls ... and the horses they love. She was the Paris contributing editor for the pan-European site Running in Heels, providing news and views on fashion, culture, and the arts for her column, “France in Your Pants.” She has also contributed critiques of foreign cinema and French politics for the politico-literary site, The New Vulgate.