Large-Format Projectors are Transforming Broadway

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

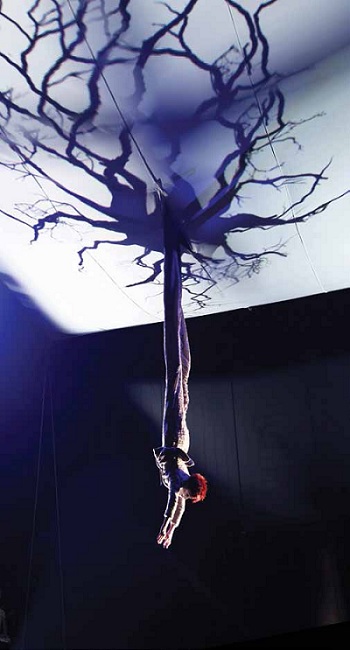

Julie Taymor’s innovative staging of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” features extensive video projections designed by Sven Ortel. The next time you settle into your seat to watch a play and the house lights dim, give a moment of thought to the scenery that’s on stage. The days of building an onstage locale by using platforms, flat walls, and movable staircases just might be numbered; a new generation of theatrical productions are using digital projectors in innovative ways to create a dynamic place for characters to interact.

“This is the future of scenery,” explained Aaron Rhyne, the video designer for the “Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder,” the current Broadway season’s hit. “It pushes scenery into new areas.”

Based on a 1950’s Alec Guinness movie, the musical details how a dozen heirs to an English fortune meet their tragic ends. Rather than using a variety of set pieces to create the wide variety of different settings — from an English garden to a prison cell — that the play requires, the show’s set has one center-stage large structure. This feature looks like an ornate Edwardian theater with a large, framed projection screen, and it’s used for a variety of remarkable effects throughout the show.

The idea is that rather than the slow process of lugging heavy, expensive scenery on and off of the stage, a projector can change the look and feel of the stage in seconds — at the tap of a keyboard. Need an outdoor scene? Pop up images of trees. Want a cozy home setting? Cue video of a crackling fireplace. The possibilities are seemingly endless.

“Gentleman’s Guide” takes this a step further. For instance, in one scene, the screen shows a video of a swarm of bees, just before they inundate one of the play’s unfortunate characters. In another, the audience sees a country vicar falling down a bell tower’s stairs, Alfred Hitchcock style. It is punctuated by the shattering of broken glass as he lands.

Visual Punchline

Timing is everything in the theater and each video effect is arranged to be the climax of how each of the doomed heirs meets his or her end. “It was the visual punchline of the scene,” added Rhyne. “It couldn’t have been done with traditional scenery.”

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for tech managers. Sign up below.

The set up that Rhyne used for the Gentleman’s Guide includes a Christie Mirage HD20K projector set up in the front of the theater and six Christie 14K-M projectors with ultra-short throw lenses behind the stage’s screen. Both devices have three-chip Digital Light Processing imaging engines and the video flow was controlled by a server that combined all the images and videos into a cohesive whole.

The play “Gentleman’s Guide” includes a Christie Mirage HD20K projector set up in the front of the theater, and six Christie 14K-M projectors with ultra-short throw lenses behind the stage’s screen. The reason for the complicated arrangement is that older venues, like Broadway’s Walter Kerr theater, where “Gentleman’s Guide” is staged, were designed for a different style of theater and almost always have very limited backstage area to set up the projection gear. To make it work, the images need to be divided into several segments to be able to fit the projectors with ultra-short throw lenses behind the stage.

“Old theaters are a big problem when it comes to squeezing in rear-projection scenery,” said Rhyne. “Newer ones almost always have more than enough room to stretch out backstage.”

Use Your Imagination

In fact, the traditional theater’s days may be numbered, because projectors can put images and video anywhere and on just about any surface — even outdoors. As part of last year’s Vivid Sydney festival, Hai Tran’s set up 17 large venue projectors in Sydney harbor and sent their images across the water to the iconic curved surfaces of the city’s Opera house. Called “Lighting the Sails,” the 15-minute looped performance piece used a projection space that was 6,000 pixels wide to cover the swooping roof and walls of the opera house with a cascade of bright colors and geometric images.

Doug Aitken’s recent video installation, “The Source (evolving),” takes video into new directions. As part of an attempt to redefine storytelling on a digital canvas, his set-up uses six projectors to create a circular image on the outside walls of a cylindrical structure. The 2,000-square foot circular video stage debuted at this year’s Sundance Festival and invited passersby just off the festival’s main drag in Park City, Utah, to stop, walk around the building and watch the action.

Aitken used six Panasonic PT-D7700 HD 3-chip DLP projectors arrayed inside the building aimed at an array of rear-projection screens on the structure’s circumference, the building took on the look of a ring of video. The installation ran at night, displaying an odd mixture of video and images onto the cylindrical screen.

With a few dozen display devices, bringing “Rocky” to life on Broadway was complicated, according to Dan Scully, the show’s video designer. An experiment by Aitken, the short videos show different conversations with global pioneers talking about in their art. As you walk around the structure, you might see two people talking over a table followed by the image of the double yellow lines of a road extending on to the horizon or shots from a concert.

Quick Change Artist

Digital scenery isn’t just for Broadway or film festivals because cash-strapped smaller and nonprofit theaters are finding that using projectors can not only add variety to their scenery, but expedite scene changes and cut expenses by replacing physical props with photons. “Projection allows us to move quickly from scene to scene without the added stress of scenic build time, set expense, stage hand labor and storage while offstage,” said Kristin Ribble, production manager for the Manatee Performing Arts Center (PAC).

Located outside Bradenton, Florida, the Manatee PAC’s 360-seat Stone Hall has a Digital Projection International Titan 1080p 800 projector that can be the equivalent of a digital scenery shop capable of turning any image or video stream into a place to act around. A recent production featured off-kilter proscenium arch digitally painted with stylized drawings of curtains and ropes for the performers to act next to.

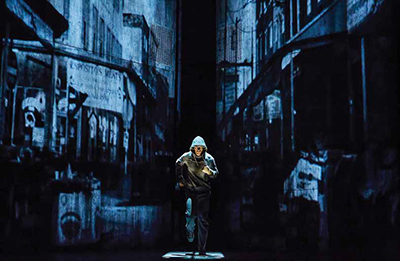

The Broadway musical “Rocky” made a high-tech debut with d3. According to the “Gentleman’s Guide’s” Rhyne, there’s a danger of relying too much on digital scenery, or using it for the wrong reasons. “A lot of producers are turning to digital scenery to save money, but it can end up looking cheap if not done correctly. Digital scenery works best when you’re imaginative and the audience can’t tell if it’s real or projected,” said Rhyne.

Doing that requires sophisticated technology that goes beyond backstage projectors. To be able to project several different things at once, include subtle transitions and make sure every cue is on time, there needs to be a server that sends the video signals to several projectors at the right time. That’s exactly where something like d3’s 4U V 2.5 server comes in.

With the ability to pump out a variety of high-quality 2,560 by 1,600 streams of video, the 4U v2.5 is part of the backstage gear for the Broadway musical version of “Rocky.” Playing at New York’s Winter Garden Theater, the show has the expected boxing ring, but its set includes two suspended 12- to 10-foot video screens fed with images from Christie and Panasonic projectors, as well as a wall of two dozen video screens. Together they serve as background scenery and display media reports of the champ’s fights.

One-Two Punch

With a couple dozen display devices, pulling off “Rocky” can get quite complicated, according to Dan Scully, the show’s video designer. “The show has a lot of architecture and infrastructure so we’re interfacing with a lot of different devices. I have to know that this machine is going to send content for that screen out of these outputs, and that the matrix will route content in a specific way for a particular scene,” said Scully.

Located outside Bradenton, Florida, the Manatee Performing Arts Center’s 360-seat Stone Hall features a Digital Projection International Titan 1080p 800 projector. The projector acts as a “digital scenery shop,” helping to create immersive special effects, digital drapery, and infinite spaces where characters can interact.. At its heart, the d3 server is a high-performance PC server that puts the emphasis on video power. Inside it has a quad-core Core i7 processor and the latest ATI graphics engine and 2GB of dedicated video memory so that it won’t choke on creating and routing multiple streams of high-definition material. In addition to being able to handle high-definition video streams, the d3 server has four slots for solid-state storage modules to hold the images and videos used in the show and can even smoothly crossfade between high-resolution videos.

Sometimes, simpler is better, such as this year’s New York City Center Encores! Presentation of “Little Me.” The 1960s Neil Simon-Cy Coleman musical was presented during the winter with a minimalist set. In fact, the show’s large orchestra took up most of the stage. Behind them was a large rear projection screen that covered about half of the back stage area. It was bordered with gilded edging to make it look like a picture frame.

Plot Postcards

Rather than projecting a simulacrum of scenery for the performers to act and sing in front of, the show’s front projector displayed images to set the mood of each scene. At one point it showed spinning Variety magazine covers, while another showed a series of post card images from different places that the Belle Poitrine character traveled during the show. It has the effect of propelling the plot forward without having any specific scenery that’s tied to the setting.

We’re in the early days of digital scenery and everyone is inventing the art as they go along. Creativity rules here because there are no rules and designers aren’t limited to a painted physical representation. This can free drama from physical constraints. Added Rhyne, “No longer does scenery have to be static, but can be changed to suit the play.”

As part of an attempt to redefine storytelling on a digital canvas, The Source set-up uses six projectors to create a circular image on the outside walls of a cylindrical structure. The 2,000-square foot circular video stage debuted at this year’s Sundance Festival and invited passersby just off the festival’s main drag in Park City, Utah, to stop, walk around the building and watch the action. Just about anything that reflects light can be scenery in this new virtual age theater. The Opera Company of Philadelphia has been particularly innovative when it comes to making the scenery fit the performance with a combination of physical and digital scenery. The company’s production of Giuseppi Verdi’s “Il Travatore” had a stage dominated by a single large 50- by 26-foot projection sharks tooth scrim. When lit from the front with stage lights, it appeared to be a solid wall, but rear-screen projection images of close ups of the singers came through when the lights were dimmed.

When the company performed Gioachino Rossini’s whimsical “La Cenerentola (Cinderella)” the stage was spare with prominent black and white stripes and a black background with gilded picture frames hung at odd angles. The key was the use of a series of projection areas in the background. The company had three Sanyo PLC XF30 projectors aimed at different places on stage to show things like Cinderella daydreaming about her prince charming with comic-book thought bubbles.

As flexible and creative as digital scenery can be, there are two potential big problems: heat and noise. This is particularly the case in an old theater where backstage space and ventilation are at a premium.

For instance, to keep scenery projectors from overheating in close quarters, designers often have to resort to setting up large air ducts above the equipment that pulls most of the heat off of the equipment and sends the hot exhaust to an industrial air conditioning unit.

“The noise and heat that projectors produce are a big deal, particularly in a small theater,” added Rhyne. “LED-based projectors are getting better and better every day but aren’t quite ready. They will be able to do the trick when they get brighter”

At the moment, hybrid projectors that don’t use traditional high-pressure lamps aren’t able to get to the brightness levels needed on the stage, but, better and brighter ones could appear in the next act of this drama.

Doug Aitken used six Panasonic PT-D7700 HD 3-chip DLP projectors arrayed inside the building in The Source. Brian Nadel is a contributing writer for AV Technology magazine, ComputerWorld, and Scholastic. He is the erstwhile editor of Mobile Computing & Communications.

info

Christie Digital

www.christiedigital.com

Digital Projection International

www.digitalprojection.com

d3 Technologies

www.d3technologies.com

Panasonic

www.panasonic.com/business/projectors/large-venue-projectors.asp

Sanyo

us.sanyo.com/Commercial-Projectors