The Grand TORE: VR for Business Just Got Very Real

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When discussing VR, thoughts often conjure up images of people wearing VR headsets or perhaps, for the more knowledgeable on the subject – a VR CAVE (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment).

But hidden away in an unassuming and unremarkable looking former TV studio on the outskirts of Lille, France – VR takes a new form.

“We believe this is the most immersive example of VR ever built,” proudly proclaimed Yann Coello, director of the SCALab laboratory (Science Cognitive Et Sciences Affectives) at the University, and coordinator of the Equipex IrDIVE investment program.

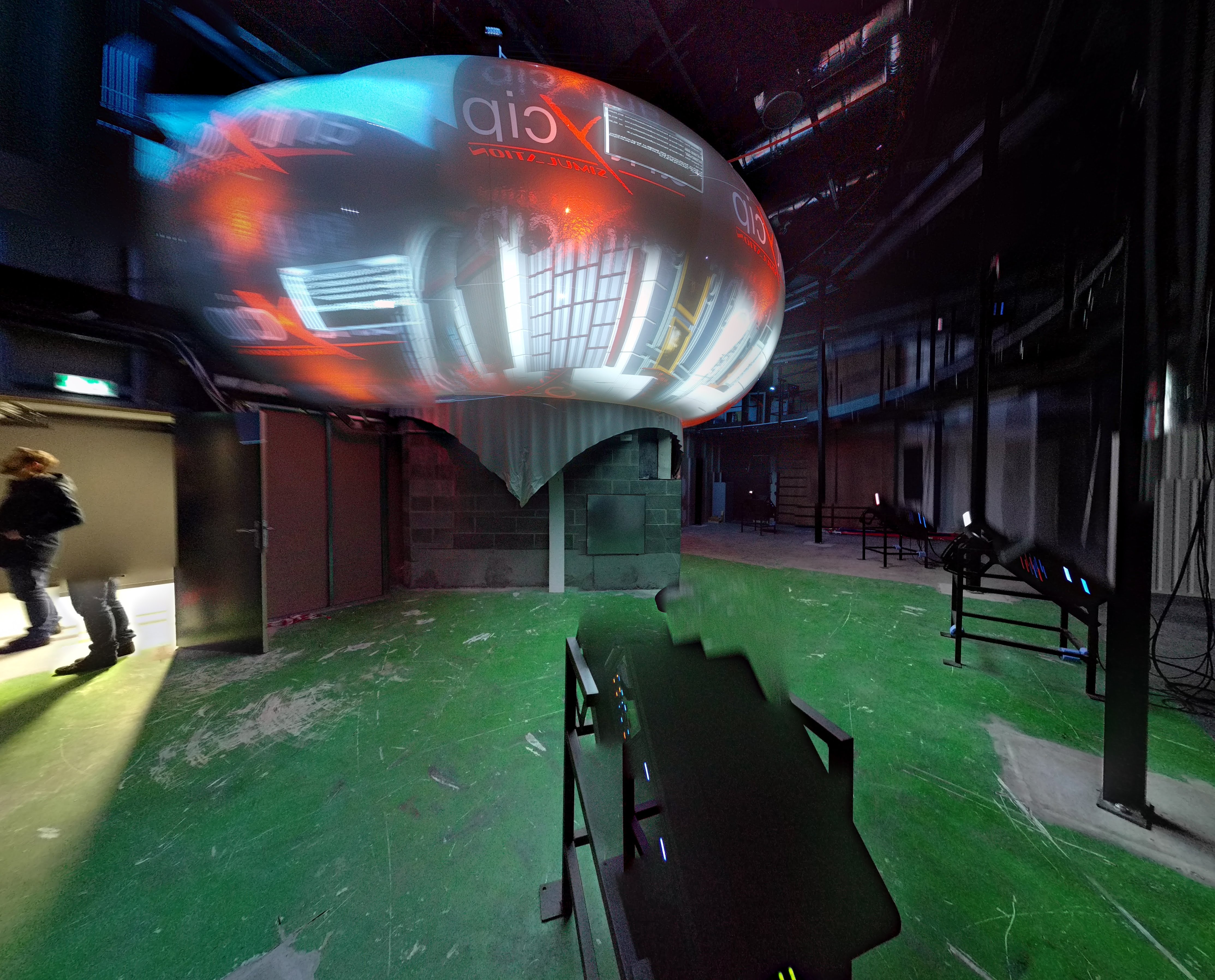

Designed, built and installed by Antycip Simulation – a French integrator of virtual reality solutions and 3D immersive rooms – The Open Reality Experience (or TORE as it’s more commonly known) marks a technological leap forward to existing flat-sided, walled VR CAVEs.

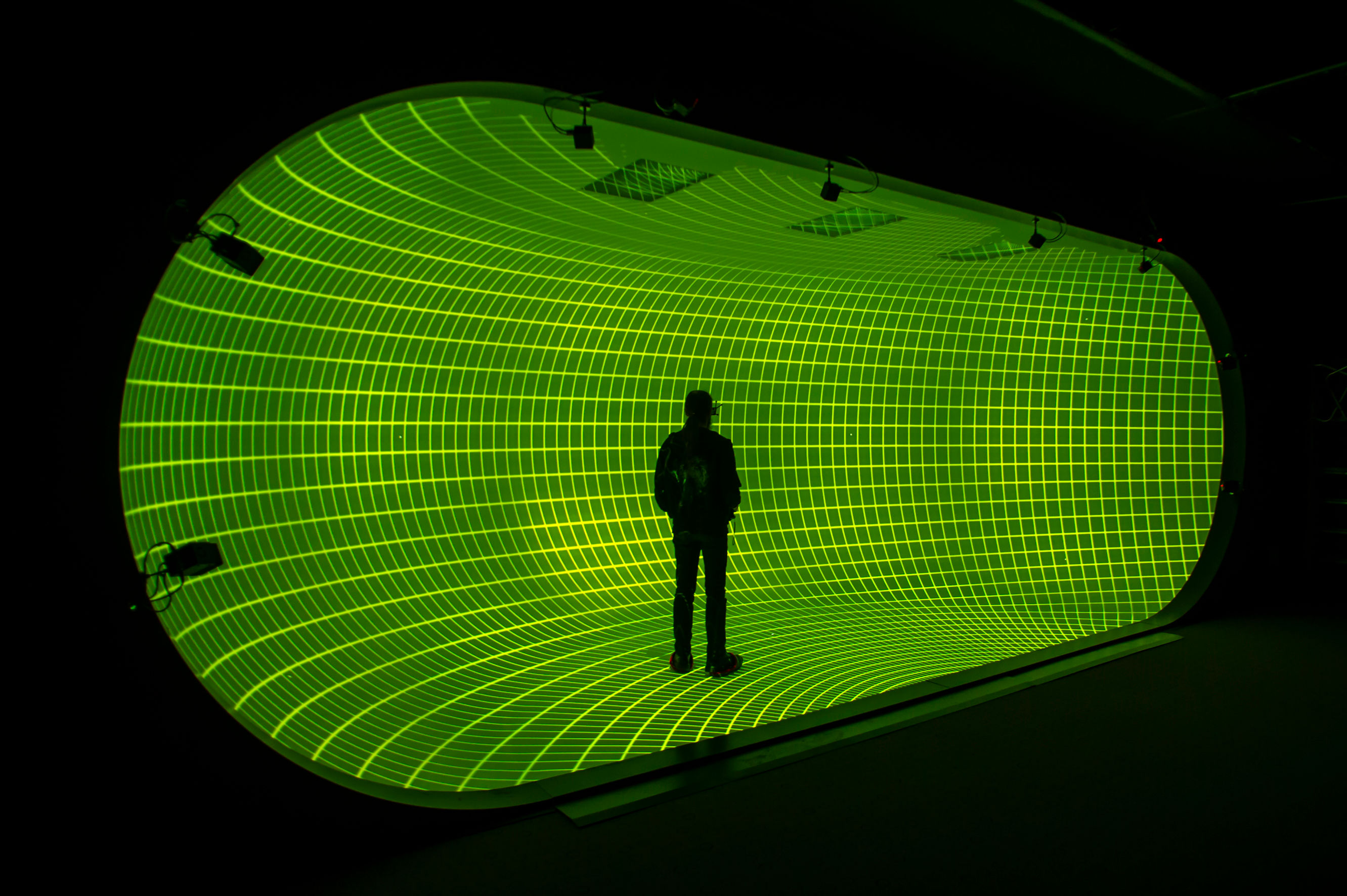

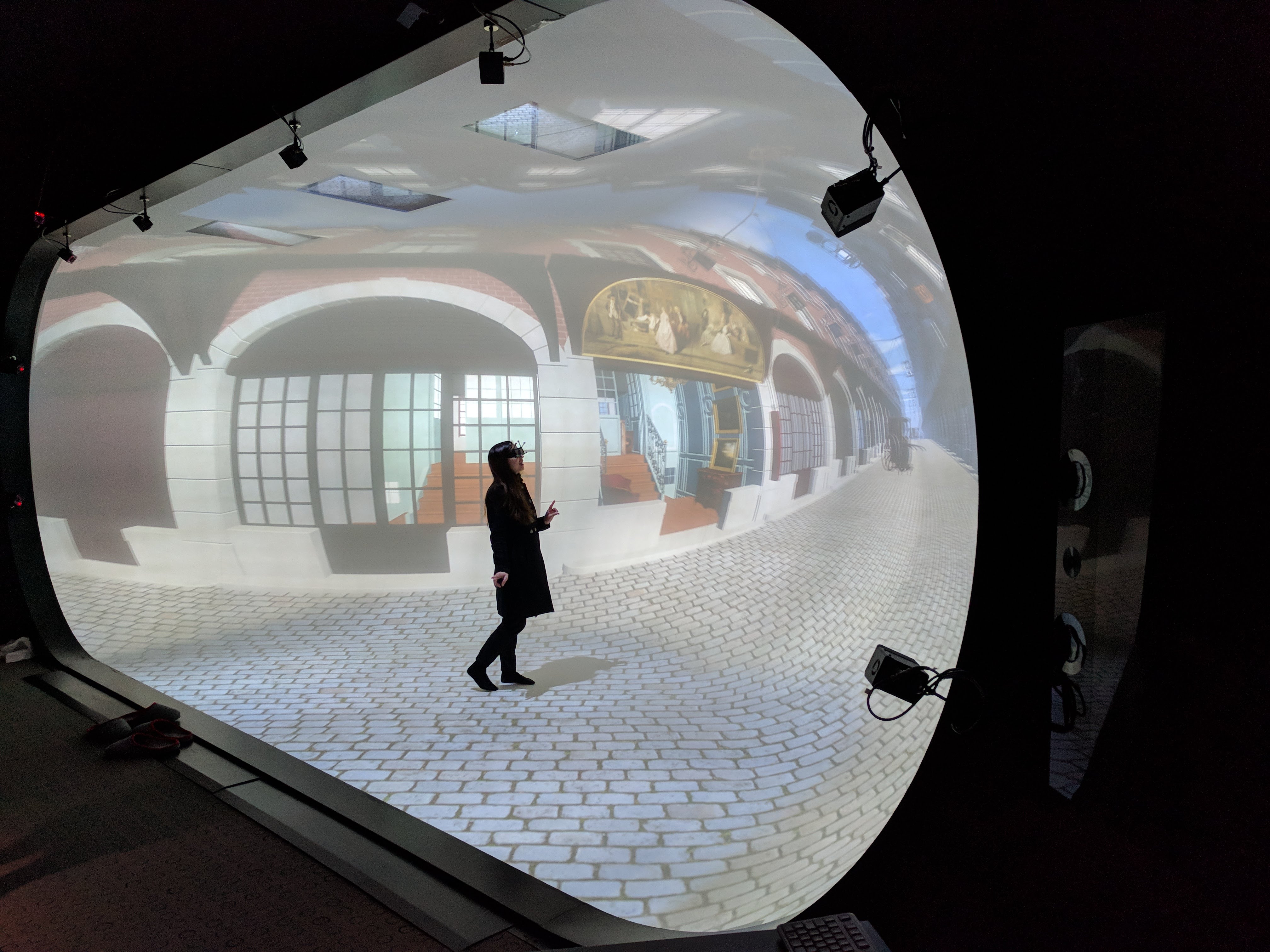

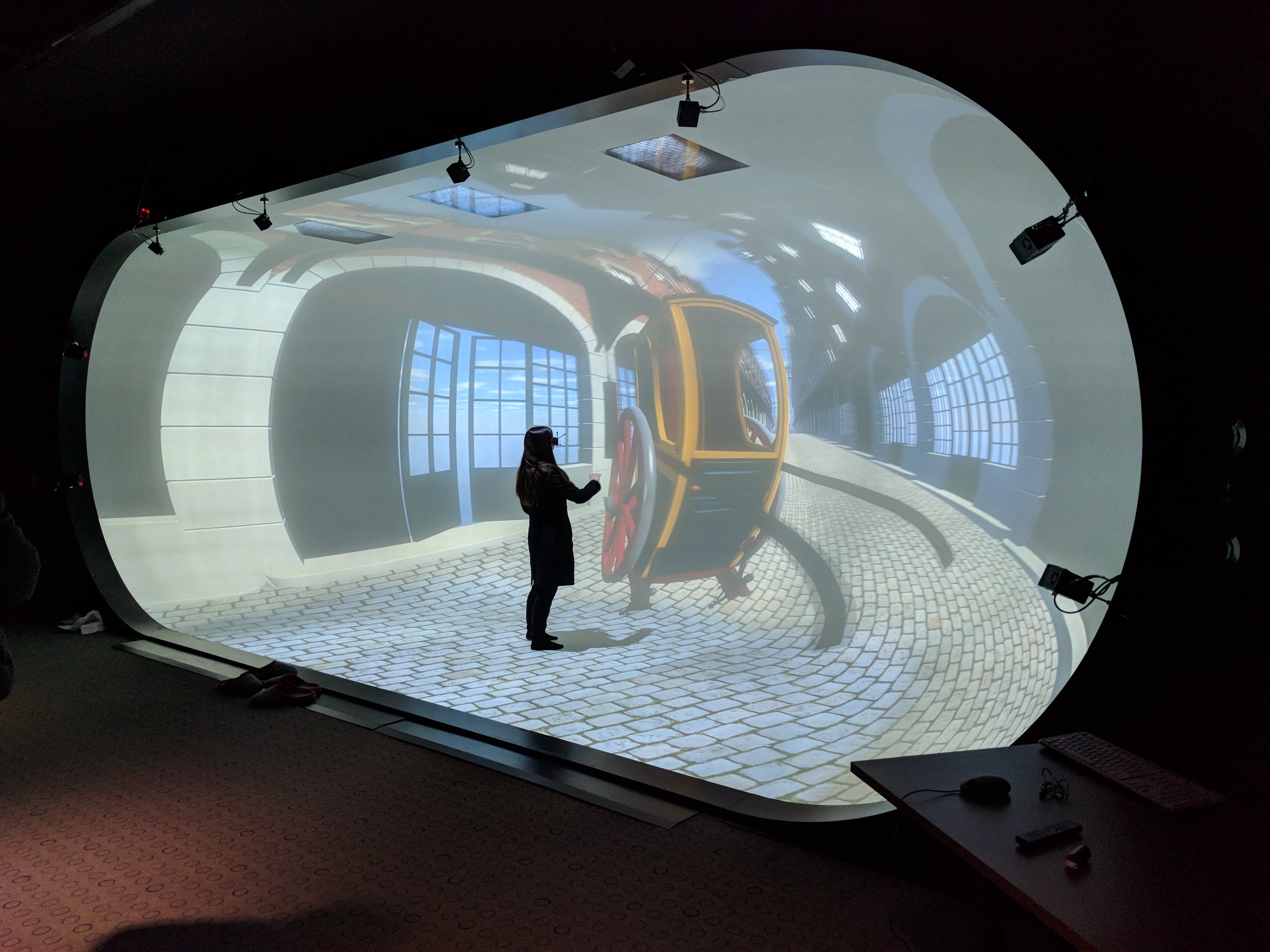

Capable of housing up to 20 people, TORE – which cost €2.5 million to build – uses a half sphere shaped painted acrylic screen (creating a room within a room) to provide a 180-degree view display with no visible walls or edges, thus removing any sense of depth and height once inside.

“The opportunities are enormous and the possibilities incredibly exciting”

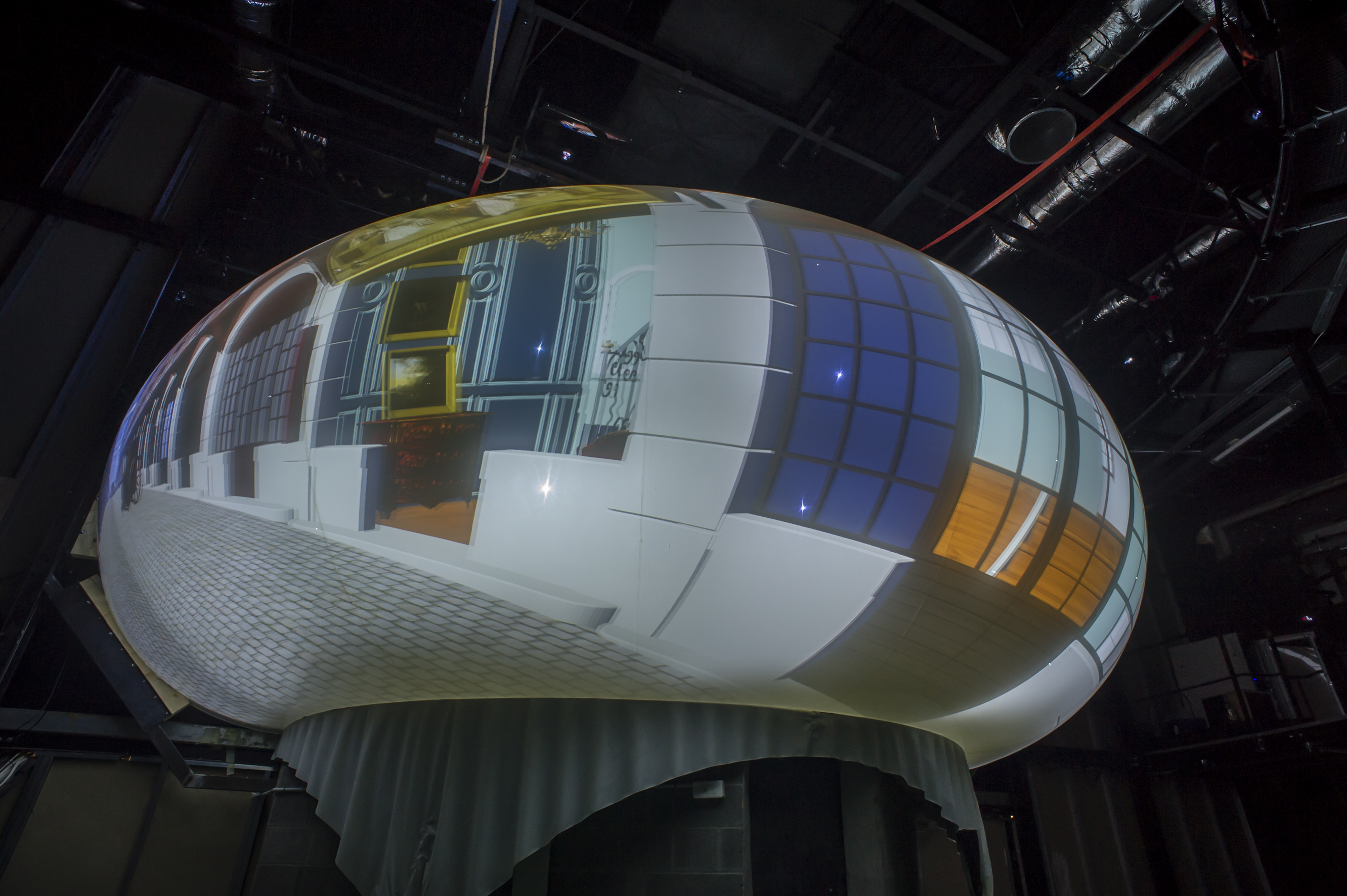

Measuring four metres high by eight metres wide, the screen is eight metres deep. The projection surface is made of eight 30mm thick curved acrylic elements and two flat ones. These had to be delivered on site before being assembled using liquid acrylic; once the material cooled down, the structure was sanded to obtain an even projection surface. The team at Antycip Simulation had to design specific tools in order to assemble the elements. Different coatings were then tested before opting for the one that would offer the best visual performance. The painting process took two weeks to complete.

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

World without boundaries

Powered by 20 Christie Tri-DLP projectors (placed out of view behind), and using custom-made mapping/warping software (called myIG), the sphere is designed to create an immersive realistic 3D environment to walk around in.

In fact, Antycip claims it’s so realistic, they’ve had to put measures in place to ensure people don’t physically walk into the walls, with the image blurring or disappearing if they get too close.

“TORE represents a major scientific breakthrough for both scientists and technologists, enabling them to benefit from a totally innovative visualisation space that goes beyond the capacities of an immersive CAVE,” gushed Coello who’s been part of TORE since funding was granted in 2012.

“It really does set itself apart from any other CAVE, annihilating the visual disruption caused by cubic shapes. A traditional VR cave would have a front, sides and sometimes a top and bottom. In these environments, the content is not always fluid because you have different sharp angles that break the feeling of immersion. With TORE there are no break in the vision and there is no other structure like this in the world.”

Seeing is believing

To get a clearer understanding, AVTE was invited to test it out for ourselves, with the firm offering three different user cases by example.

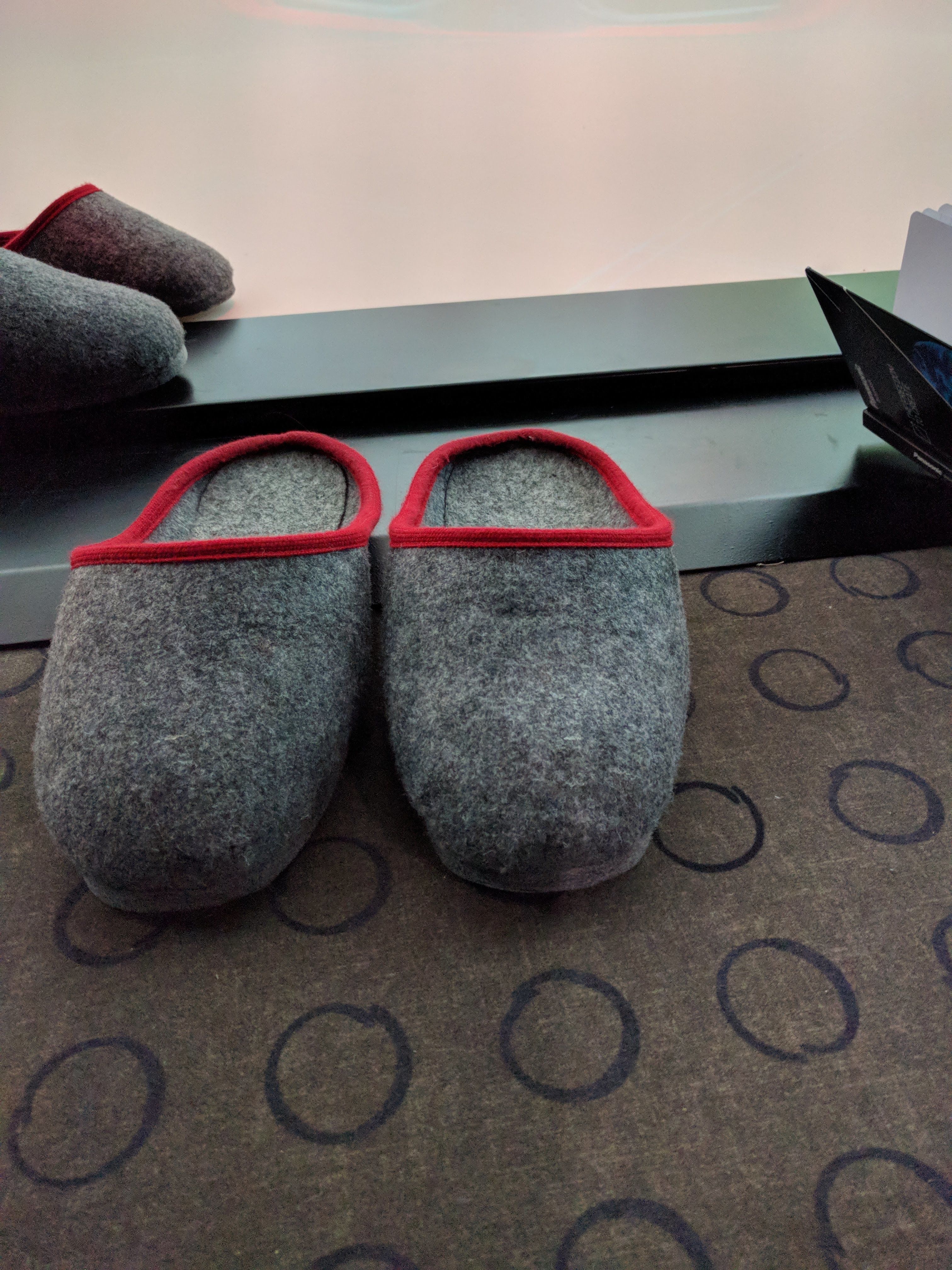

But before entering the half sphere – there were two things required by way of preparation.

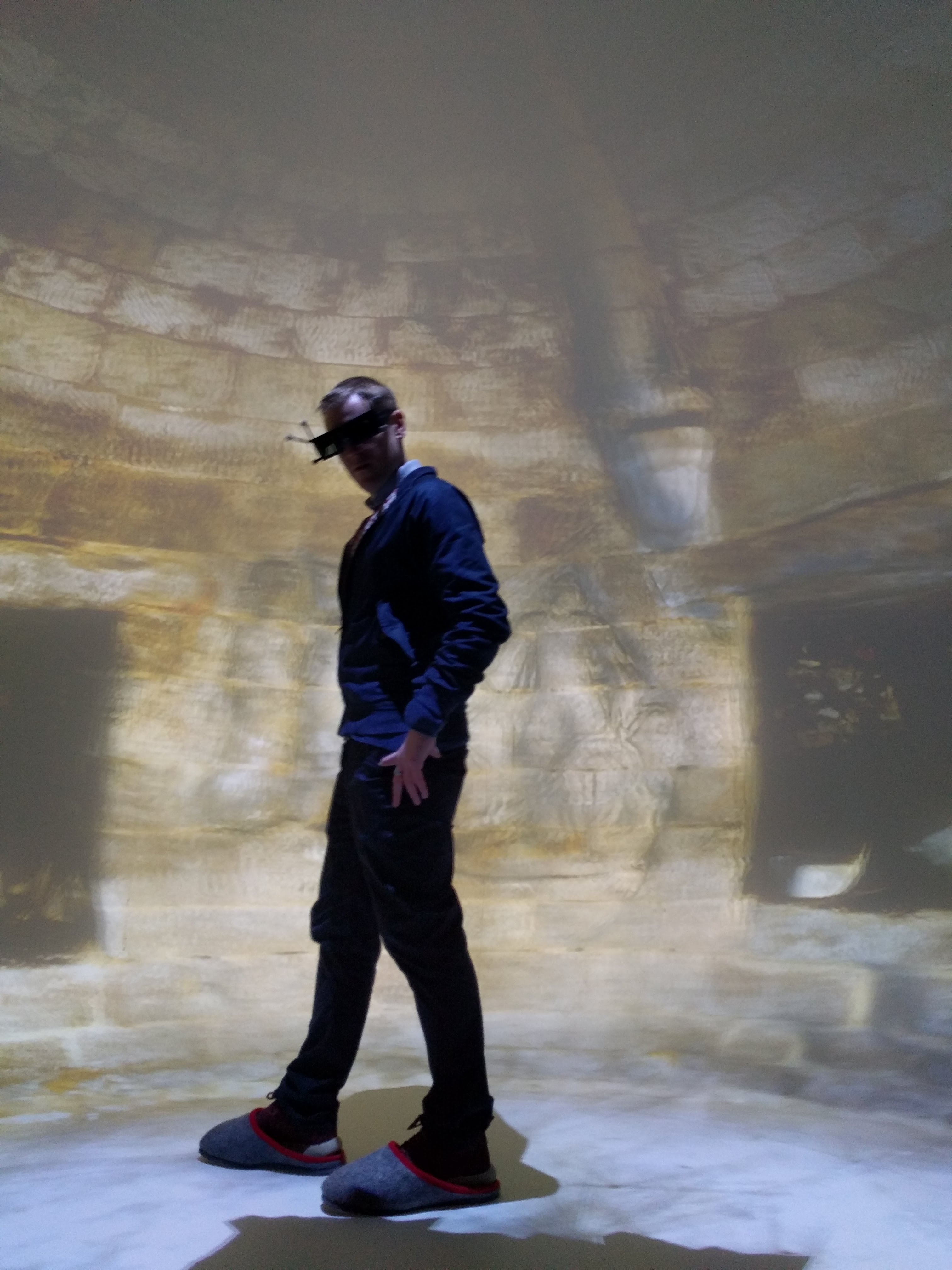

Firstly, due to the importance of keeping the acrylic CAVE in tip-top shape and the VR illusion unhindered, all those that step onto its surface must wear a set of slippers.

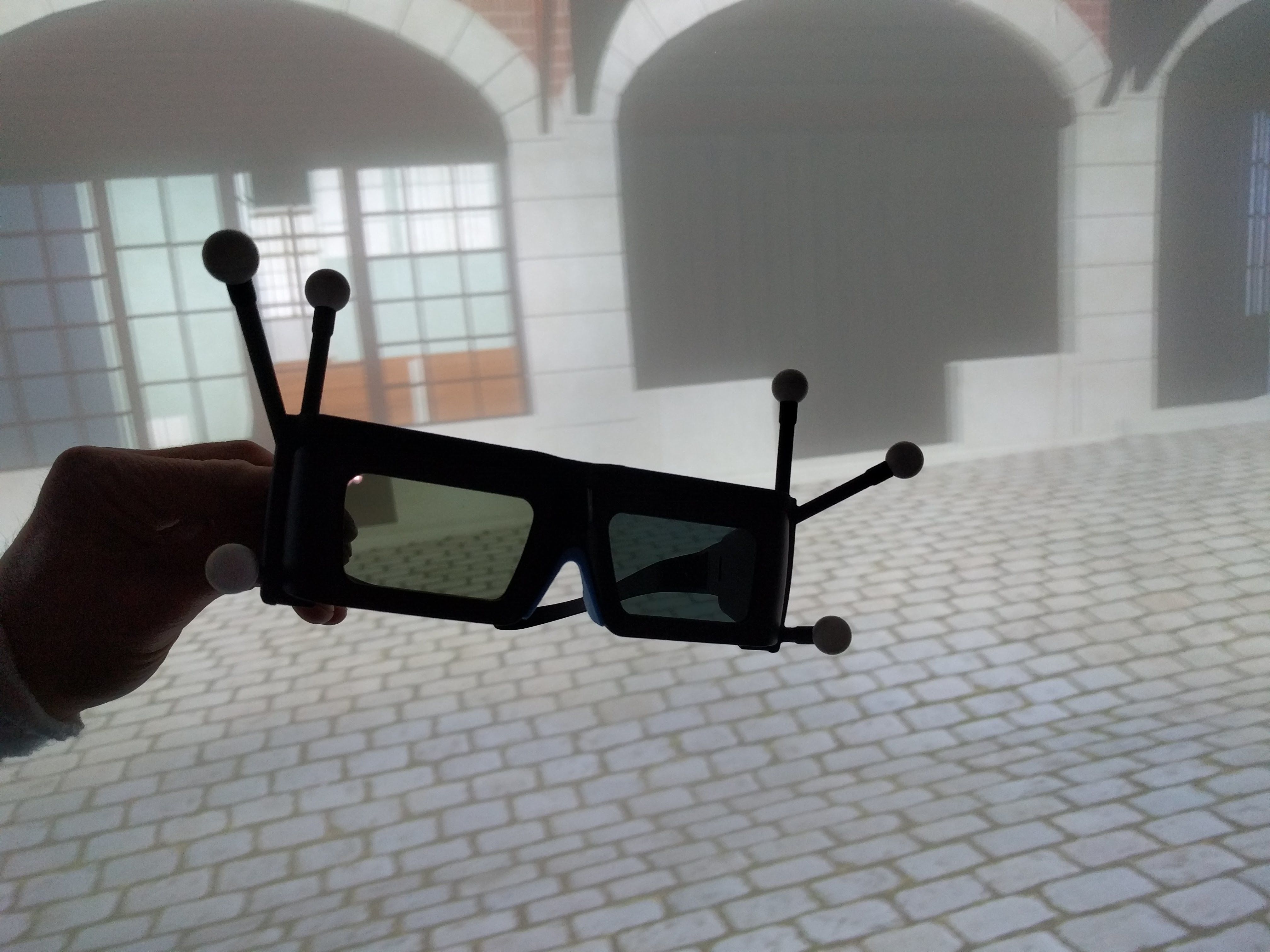

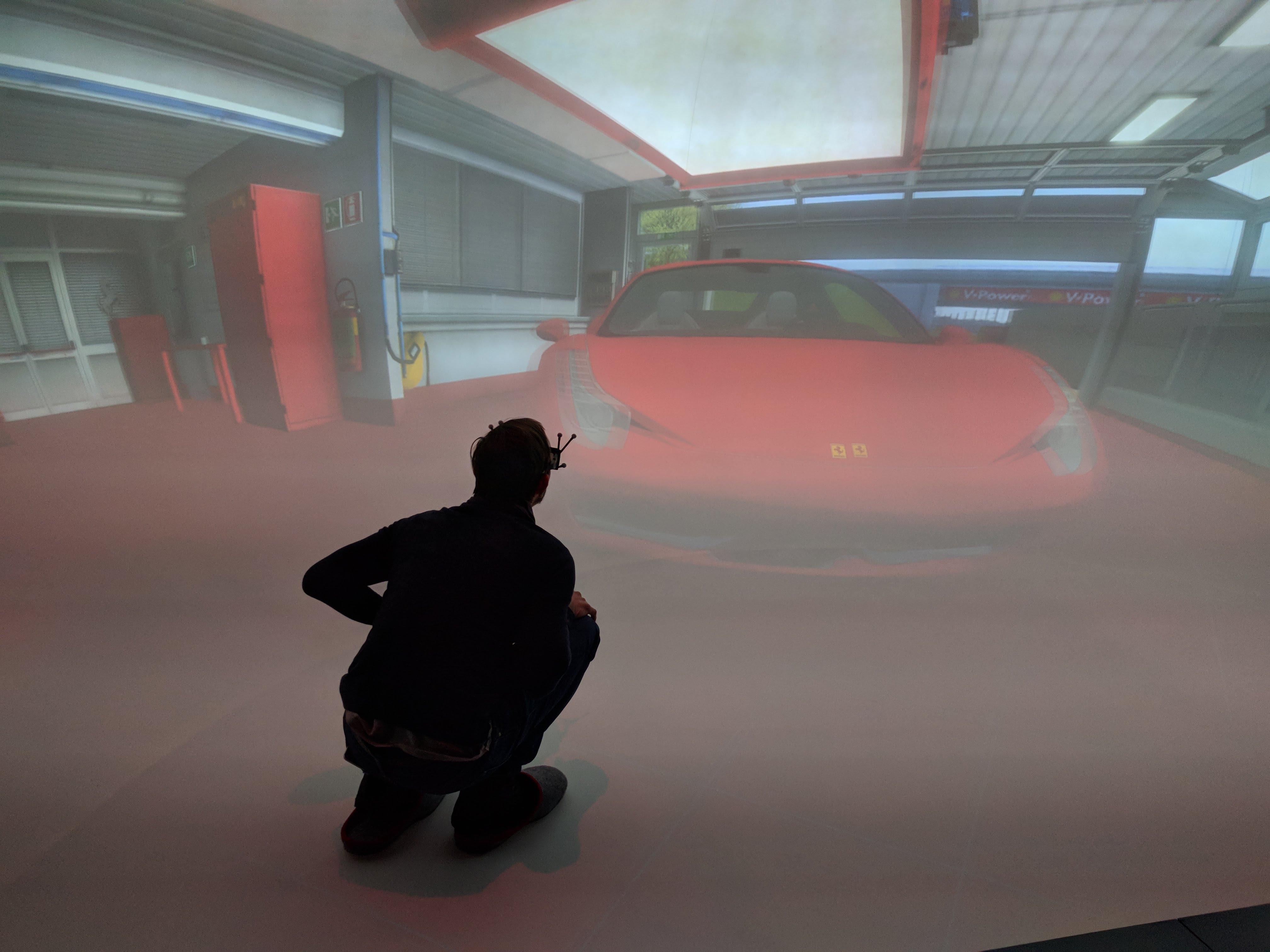

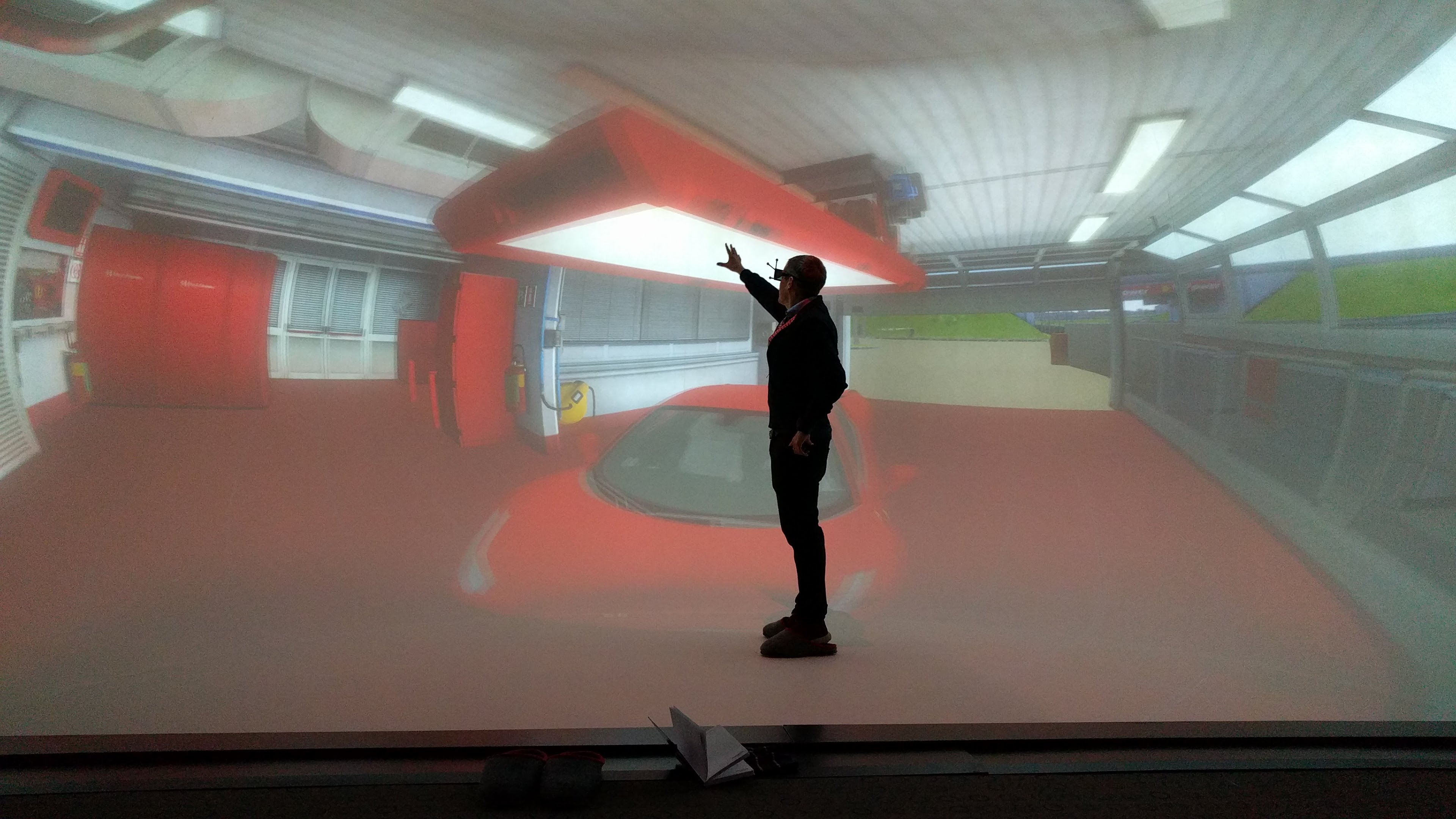

Secondly, and most crucially, users must don a pair of 3D glasses – comparable to those you wear when viewing a 3D movie at the cinema or at home. But, as you can see from the images, these are no ordinary 3D cinema glasses. Equipped with infrared sensors (see picture), these communicate directly with TORE’s tracking system (hidden), which follows the individual’s every movement, including where they happen to be looking, adjusting the image viewed accordingly.

"The glasses decrease visual fatigue, and more readily reinforces the immersion in the virtual world being projected"

VR without the headache

The glasses, so says Yann, provide significant benefits over VR headsets, removing eyestrain, allowing for longer usage, and improving balance due to the wearer being able to see their own body.

“The glasses decrease visual fatigue, and more readily reinforces the immersion in the virtual world being projected,” Yann explained. “After 10 minutes wearing a VR helmet or goggles, it can cause you some problems.

“The main difference with TORE is that you are physically embedded into the scene. So, it’s your body in the scene. When you wear a helmet you cannot see yourself, only the visual scene. Here it all feels real. There’s no feeling of claustrophobia and no feeling that you could be about to trip over something.”

Down to a fine art

With my slippers (forcing me to shuffle around like a moody school child) and glasses on, I stepped into TORE and was immediately transported back in time to 18th century Paris.

The location was Pont Notre-Dame, the most famous formely inhabited bridge in the history of Paris.

Today, the bridge is an empty open space providing pedestrians and vehicles with scenic 360-degree views of the river Seine and surrounding areas – including Notre-Dame cathedral. Back then however, the bridge (think Florence today) was lined with 60 or more buildings and a hive of activity. One of those buildings was (is) engrained in Parisian history – a tiny art boutique called Au Grand Monarque (later A la Pagode), occupied by Parisian art trader Edmé-François Gersaint.

“Careful where you walk,” someone shouted from behind me. “They didn’t have toilets back then”

Despite being demolished by 1788, a multidisciplinary team of scientists specialised in computer and historical sciences and 3D computer graphics professionals were able to bring the boutique back to life digitally for people (such as historians) to view, walk around and experience for themselves today.

“It was rebuilt using a 3D scanner,” explained Yann. “We have taken a lot of different examples from various different pieces of art and literature. It’s exactly how it was at the time, with real images of the pictures on the wall and the size and design of the building.”

Mixed reality

Being a digital recreation, the experience of walking around the boutique was a surreal one – like being absorbed into a computer game or animated film (think Mary Poppins or Tron). But that’s not a criticism.

The objective of being truly immersed was achieved instantly – with no visual boundaries to be seen and a real sense of space and freedom.

The tracking system worked with minimal (if any) latency, ensuring that views will always remain clear and adjusted accordingly.

From there, the setting was changed by a watching technician, sending me out into the street to give me a full view of the boutique from the bridge, whilst also taking in the sights of the surrounding areas.

“Careful where you walk,” someone shouted from behind me. “They didn’t have toilets back then.” I checked, but it was all clear – perhaps something to add in the future? Perhaps not.

A room with a view

The second of the three-user case demonstrations transported me to a room inside the Château de Selles in Cambrai, which was once used as a prison and not accessible to the public.

Unlike the boutique, the visuals creating the room were put together using a 3D camera scanner. The small room provides the opportunity to walk around as if you were there; crouching down to view different carvings and marks created by prisoners during the era it was used.

“It’s all real content, so you are seeing what’s actually there,” said Yann. “For many this would be the only opportunity to experience, view and study this room.”

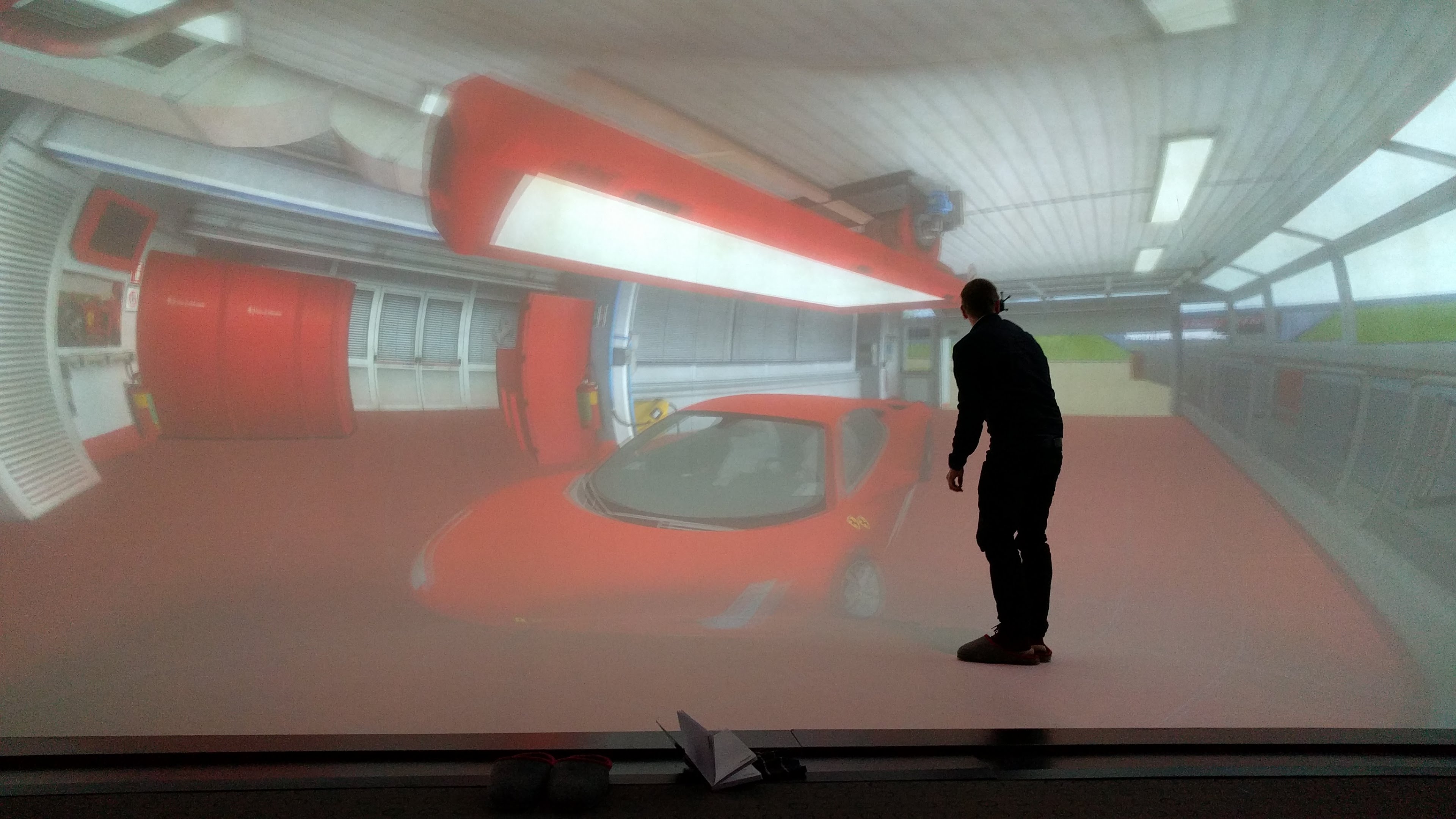

The third and final room, reverting back to digital again, was a garage holding a Ferrari. This scenario provides the ability to explore the car with great detail, viewing from every angle possible. The 3D effects were so real you could almost feel the car. I even repeatedly moved my head to avoid banging it on an overhead light.

Business case

All three examples are designed to demonstrate just some of the business cases the project can provide.

In total, the project has received €17m in funding as part of a ten-year plan (see box out). Antycip is aiming to have the business commercially operational (and viable) within the next couple of years and is already in discussions with prospective clients.

Its main area of focus includes academic research (computer science, historical science and social science), but the company believes there are some big opportunities for businesses and governments when it comes to design.

This is an expensive toy and needs to be monetised

“This is an expensive toy and needs to be monetised,” said Olivier Colot, CRIStAL laboratory director.

“The idea is to try and emulate some of the ideas with brands. It could be architecture, it could be automotive, oil and gas, telecoms, energy – you name it. The idea would be to bring some funding from projects.

He continued: “If you’re an architect, you can use TORE to make sure the design, the space the lighting – everything is perfect. Perhaps you’re a car manufacturer and you want to test out a new design, so you allow consumers to take a look and sit inside first. It’s basically a decision-making tool. If Audi for example wants to have a new door and they want to make sure it slams correctly, they can test it in a VR setting first.

“On a bigger scale, if you’re the mayor of a city, you could look at and test out different examples of designs – bringing in people involved with the building of cities, politicians and people within public transportation.

“The opportunities are enormous and the possibilities incredibly exciting.”

What’s next?

With audio already possible, adding to the experiences (although not demonstrated on our visit) the next phase of the project will be in the form of interaction during the VR experience. This would provide feedback and the sensation of touching something physically.

“We’re not there yet, but that’s the goal going forward,” said Yann, concluding the tour.

With more than 100 researchers and companies all occupying its head office, all focused on advancing gaming, AV, VR and AR technology, it may not be too long before VR again takes another important step forward.