Planning Your Next Technology Upgrade

Principles of IT Asset Management and Lifecycle Planning Can—and Should—be Applied to AV Technology. Here’s How Some Technology Managers Do It.

Nothing lasts forever. New technology replaces the old, creating both opportunities and challenges for tech managers and users.

The circle of life isn’t reserved for living creatures; it applies to inanimate objects too. Product lifecycles have been discussed in marketing literature since 1965, when it was first introduced by Harvard professor Theodore Levitt. The stages include product introduction, growth, maturity, and decline. Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) provides a framework for manufacturers to plan the development, marketing and sales efforts for new products. A parallel concept has evolved in modern organizations to deal with the lifecycles of technology-based products once they’re procured and deployed in an enterprise. Technology Lifecycle Management (TLM) is a tool applied by technology users to plan for the acquisition, disposal, and replacement of products and systems as these products approach the end of their useful life. While it’s most often associated with IT systems and equipment, the concepts are increasingly relevant for most AV gear.

If It’s Not Broken, Fix It

Technology Lifecycle Management runs counter to the old adage, “If it’s not broken, don’t fix it,” except that more often than not, tech products are replaced (or “refreshed”) rather than repaired. Waiting until a device stops working is usually the most costly approach, when you consider productivity loss and the cost of downtime while a replacement is sought, installed, and users are re-trained. Savvy tech managers know that preemptive replacement is more cost effective in the long run than repair, especially given the commodity status of many technology products.

Conventional wisdom once suggested that if a repair was estimated to cost 50 percent or less than the amount you paid for an item, it was usually better to have it repaired. In today’s fast evolving technology environment, however, dropping prices and accelerating obsolescence makes the “50 Percent Rule” less applicable. Replacement products are often cheaper; or for the same cost, you’ll likely get more features and better performance.

Replacement strategies carry another cost too—what to do with all of the old technology. Especially with technology products, which can be filled with environmentally unfriendly materials, disposal can be an expensive proposition.

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for tech managers. Sign up below.

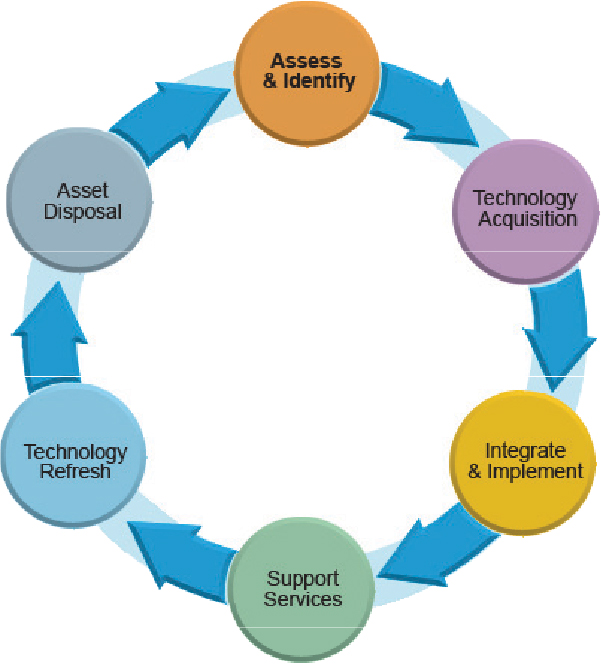

Corporations, government organizations, and educational institutions—typically the largest users of technology—are realizing the advantages of a structured TLM approach. Over the last several decades, sophisticated systems of tracking AV and IT “assets” and budgeting for their replacements has become a more formalized process. Some third party IT services providers, like Herndon, VA-based GTSI, help organizations plan technology acquisition and deployment on an outsourced basis. In 2007, GSTI introduced the TLM concept to its government customers, defining TLM as “a multi-phased approach that encompasses the planning, design, acquisition, implementation, and management of all the elements comprising the IT infrastructure.” According to GTSI, the TLM process is broken down into six phases:

- Assessment and identification of business objectives and appropriate application of technology

- Technology acquisition specific to IT infrastructure requirements

- Integration and implementation

- Support services (like custom warranty and maintenance packages, help desk services, and systems monitoring, etc.)

- Technology refresh to ensure upgrades are timely and relevant

- Asset disposition under pre-negotiated terms

ICT services provider Dimension Data offers a TLM approach that helps clients ensure that IT assets continue to support their businesses over their lifecycle. Their Technology Lifecycle Management Assessment is an IT infrastructure asset assessment service that discovers installed assets on the network, identifies their lifecycle status, and determines maintenance coverage. According to the company, this service also ensures that organizations don’t expose themselves to unnecessary risk, by helping to align their network estate with configuration, security and patch management best practices.

Where to Start

Regardless of whether you do it yourself or outsource it, any technology lifecycle management strategy begins with a comprehensive database of all AV and IT products you wish to track. Beside basic device info (brand/model, purchase price, serial number, IP address, MAC address, etc.), include time-based information such as each product’s manufacturer warranty period, date of purchase, date put into service. Then you’ll need to establish a replacement schedule for specific products. A common guideline is the warranty period offered by product manufacturers. The premise is that products should last at least as long as the warranty period, which is usually painstakingly calculated by the product manufacturer. Warranty periods, however, do not necessarily coincide with product obsolescence trends; especially in high tech, it’s not unusual for a product to become obsolete “old technology” even before its warranty period expires.

For 14 years, Dimension Data has published its “Network Barometer Report.” The study reviews networks’ readiness to support business by evaluating the potential security vulnerabilities and configuration variance from best practices, operating system version management and lifecycle status of the discovered network devices. Their most recent report, published in June 2012, concluded that 45 percent of the networks of the nearly 300 organizations they assessed during 2011 will be totally obsolete within five years. That’s an increase of 38 percent over the previous year. In addition, of the devices that are now in the obsolescence cycle, the percentage that are past the date after which you can no longer buy the product (called “end-of-sale,” or EoS) increased dramatically, from 4.2 percent in 2010 to 70 percent in 2011. As explanation for this change, the report suggests that equipment manufacturers have moved more products to EoS to make room for newer products.

But product obsolescence is not the only thing that affects replacement lifecycles. According to Steve Kleynhans, vice president of the mobile and client computing group with technology analyst firm Gartner, lifecycles of related products and economic factors play a role too.

Product obsolescence is not the only thing that affects replacement lifecycles.“A decade ago, PC lifecycles were pretty consistently set at three years for desktops and three years for notebooks,” said Kleynhans. “This was driven by the continual need to upgrade hardware to run new operating systems and new versions of applications. Three years roughly matched the cycle times of Windows releases, new versions of Office, and new hardware components, like memory and processors. Over time desktop lifecycles started to extend as companies started questioning the expense of proactive hardware replacement and by 2006 desktops were typically being kept for four years, while notebooks remained mostly at three years. Then the recession hit in 2008/2009. Organizations held back on PC purchasing and lifecycles were frequently abandoned. It was not uncommon to find companies in 2010 with machines that were six or seven years old. With the need to move off of Windows XP and transition to Windows 7, companies started to restore some order to their lifecycles and for the most part we have seen the desktop lifecycle split between four and five years, while notebook lifecycles are split between three and four years.”

Of course, companies must temper their replacement policy guidelines with recognition of what really happens in the field with technology assets, according to Kleynhans.

“Extending the life of notebooks has proven to be problematic, since there is a marked increase in breakdowns due to wear and tear in the fourth year of service. Desktops don’t generally have a similar problem and most will never see a hardware failure in five years of service. However keeping devices somewhat current is still desirable as it enables the introduction of new functionality, keeps the variations across the fleet to a minimum, and provides improvements in performance and power efficiency. It also can be important for the corporate image as having ‘ancient’ devices can reflect poorly on the company and can make it harder to attract younger workers,” observed Kleynhans.

Sweat It or Forget It

Whether it’s tight budgets, or pressure from executive management, sometimes tech managers are tempted to postpone replacement of products that seem to be working fine, but are near the end of their useful life. “Sweating” an asset refers to extending or maximizing the useful life of an existing technology asset, thereby avoiding (or postponing) the need to replace it until absolutely necessary. But according to some experts, it can be a risky strategy. “While some organizations appear to be wising up to the financial benefits of intelligently ‘sweating’ network assets, if the cost savings aren’t weighed against the risks, they could also be exposing themselves to serious business continuity issues,” said Raoul Tecala, Dimension Data’s global business development director for network integration.

A simple cost analysis can help determine if replacement makes more sense than trying to eke out a few more productive years of service. Microsoft MVP (Most Valuable Professional) and SharePoint expert Robert L. Bogue suggests using a cost analysis approach that compares the cost of supporting an existing technology asset with acquiring a new one. Support costs include:

• Reduced productivity—How much will be lost in a given year due to the lack of speed in the existing solution?

• Down time—The cost incurred if the product stops working multiplied by the probability that the down time will occur in a given year.

• Support Agreements—If the device is beyond its warranty period, and it is necessary to maintain a support agreement for it, the cost of the agreement should be considered.

• Support Calls—If the device is beyond its warranty period and you elect to pay for service calls, the cost of those calls multiplied with a best guess estimate on the number of calls.

• Staff Support Time—If your IT staff will have to invest time in supporting the solution, it should be added to the overall support costs. Costs associated with acquiring a replacement include:

• Acquisition cost—The actual cost of the replacement, including any taxes or freight.

• Setup cost—The cost to get the device set up on the network to replace the existing device. This should include any fees, as well as staff time, multiplied by a reasonable rate.

• Learning curve—The time that your staff and the users will need to understand the new device multiplied by a reasonable rate to convert it to a cost.

• Risk—Every new device has some risk. Assign a dollar value to the risk that the new system will not work or will not work as intended. The newer the device being proposed for acquisition, the more risk is associated with it.

• Support costs—The cost of supporting the item for the first year. Include agreement costs, support call costs, and staff time costs. Simply by comparing the two numbers side-by-side, it’s easy to see whether a replacement makes financial sense or not.

Clean Sweep or Staggered Swap?

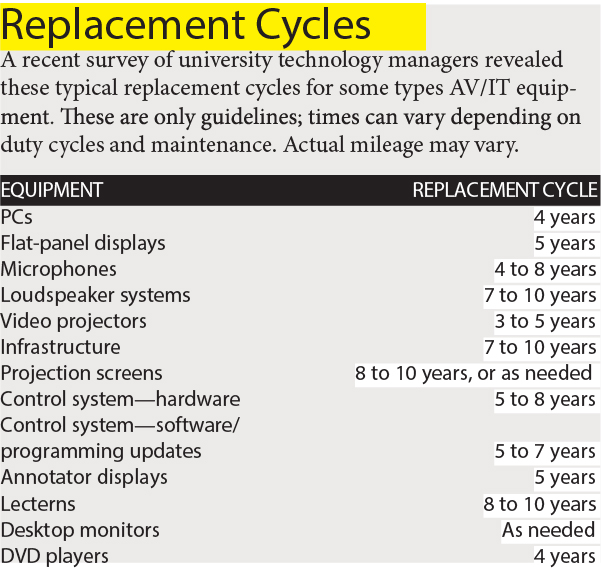

One approach followed by many companies is to replace technology products on a staggered basis; for example, replacing one-third of all PCs each year over a period of several years. However, this results in a mix of PCs, which may have a variety of operating system versions, features, and capabilities—creating a costly support desk nightmare. A better approach, according to some technology managers, is a fullsweep comprehensive replacement and upgrade program. The replacement cycles of different categories of products can then be staggered (for example, PCs one year, projectors the next year), so that budget impact on an annual basis is spread out.

Technology as a Service?

Planning and executing a technology lifecycle management program can be a real resource drain for any technology manager. But there are signs that the things may be improving. As more products move toward software-based control, it’s possible that a technology upgrade for many network appliances could be as simple as updating your mobile phone. And as cloud-based applications, infrastructure, and services continue to proliferate, there may actually be fewer physical hardware devices to have to track and replace. Of course, there will always be the tangible endpoint products with which users must interact and will, over time, simply wear out (like portable devices and user interfaces), but these are also the products most likely to become commoditized and easy/ cheap to replace without major disruption to business operations.

Mark R. Mayfield is an independent consultant, analyst, and writer in the communications technology industries.

Cisco’s End of Life Milestones

Technology giant Cisco is one of many tech companies who have a formal “end-of-product- life policy” that helps tech managers plan for migration to alternative products and services. As long as customers have a “current and fully paid” support contract with Cisco, their guidelines stipulate that customers will receive six months advance notice of a product’s end-of-sale date, which is the last date the product can be ordered. After that, customers are guaranteed access to technical support for the discontinued product five years beyond the end of sale date for hardware and operating systems, and three years for application software. Also, spare parts will continue to be available for five years.

To minimize confusion, Cisco posts actual end-of-life calendar dates on their website, including the following milestones:

* End-of-Life Announcement Date—The date the document that announces the end of sale and end of life of a product is distributed to the general public.

* End-of-Sale—The last date to order the product. The product is no longer for sale after this date.

* End of Phone Support—The last date of free (contracted) phone support as part of the product warranty. After this date, all phone support services for the product are available only with additional charges or support fees. In some cases, support may not be available.

* Last Ship Date—The last-possible ship date that can be requested for the product. Actual ship date is dependent on lead-time.

* Last Date of Support—The last expected date to receive service and support for the product as entitled by warranty terms and conditions. After this date, all support services for the product are unavailable, and the product becomes obsolete.

Tech Tock: Gartner’s IT Market Clock

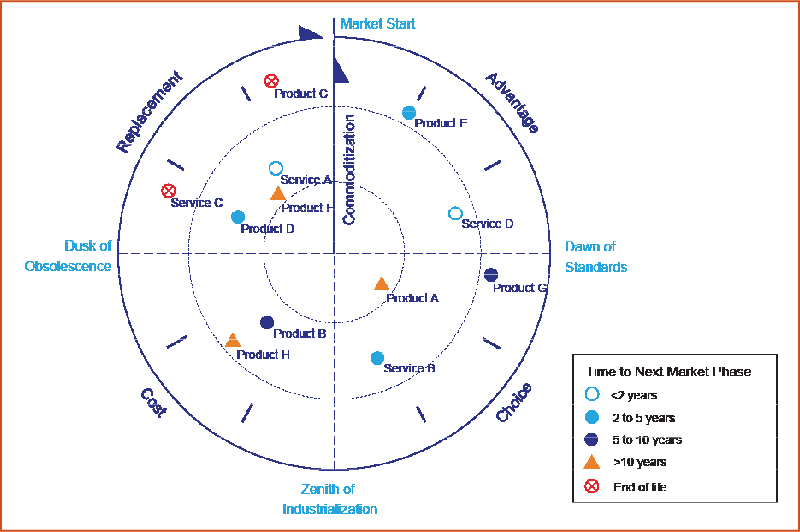

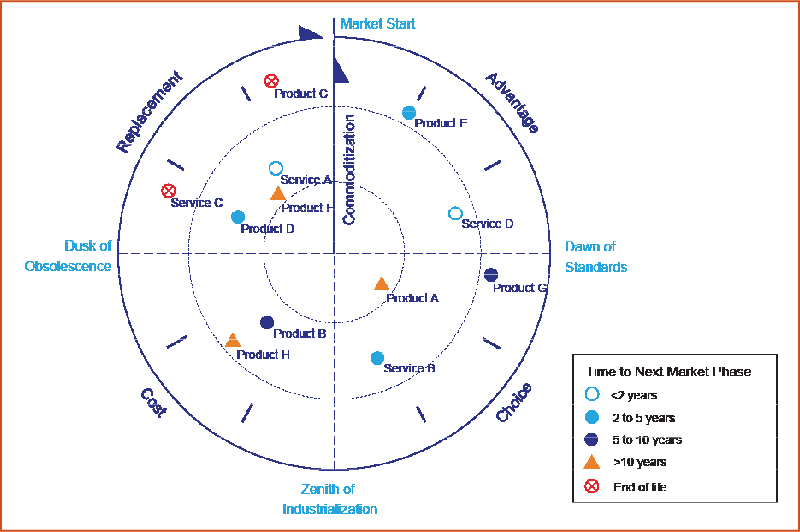

In 2009, technology analyst firm Gartner introduced its IT Market Clock, a decision framework to assist IT and business leaders evaluate and prioritize their IT investment and divestment activities throughout the entire asset life cycle.

The Market Clock provides IT leaders with a full-lifecycle portfolio view of IT products and services in terms of relative market maturity and commoditization levels. It’s based on the idea that every IT product and service has a finite useful life, and must eventually be retired or replaced.

Gartner produces IT Market Clocks for a number of product or asset categories, including:

• Application Development

• Application Services

• Client Computing

• Communications Services

• Database Management Systems

• Enterprise Mobility

• Enterprise Networking Infrastructure

• ERP Platform Technology

• Financial Management Applications

• Human Capital Management Software

• Higher Education (vertical market-focused)

• Infrastructure Protection

• Programming Languages

• Server Technologies

• Storage

Gartner’s IT Market Clock plots the current state and predicted lifecycle of IT products or services within a marketplace. It uses a clockface metaphor to represent relative market time and how technology assets are positioned based on their progress through their market life cycles and commoditization levels. A symbol (circle or triangle) is used for each asset also demonstrates the time it will take for each asset to transition into the next of the four market life phases:

Advantage—From 12:00 to 3:00, when the market typically moves from an emerging to “adolescent” status, when levels of demand and competition are typically low.

Choice—From 3:00 to 6:00, when the market typically moves from adolescence to early mainstream. This is the phase of highest demand growth, during which supply options grow and prices fall at their fastest rate.

Cost—From 6:00 to 9:00, when the market moves from early mainstream to mature mainstream. During this phase, commoditization is at its highest level and costs will be the strongest motivator in most procurement decisions.

Replacement—From 9:00 to 12:00, when the market moves from mature mainstream, through legacy and to “market end” (after which, the technology is no longer viable to procure or use). Procurement and operating costs will steadily rise and organizations should seek alternative approaches to fulfilling the business requirement.

The relative commoditization determines the distance from the center of the IT Market Clock; products or assets further from the center are more commoditized.

Also included: commoditization, the level of standardization, and the number of suppliers. The supplier information defines the range of choice available to buyers, and their ability to take advantage of the interchangeability/interoperability yielded by standardization.

Access to appropriate skill is also included. Every product and technology requires some level of internal capability to use it. The ease with which these capabilities can be obtained directly affects the internal cost of switching suppliers.