Beyond the Tech: Problem Solving Against the Clock

It takes tenacity—and sometimes a visit to the local gun range—to accomplish the impossible.

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Many years ago, I faced an insurmountable task for a high-profile project. Through a combination of cleverness and tenacity, I was able to make it happen. And it all started with a bit part in a music video.

I started my business as a sound contractor, designing, installing, servicing, and renting sound systems. (A shout out to Sam Ash, with whom I partnered with for about 15 years.) I had been working for Billy Joel and his production folks putting in sound systems at their offices and homes. That's when they asked me to act in one of Billy's music videos.

[Beyond the Tech: Do You Go the Extra Yard?]

Initially, I said no but eventually acquiesced. I spent two grueling days filming, one day on a 350-foot garbage scow leaving Manhattan and the other at various locations. Yes, you can see me early in the “The Night is Still Young” music video. When Billy opens a door, I swing from a crossbeam and follow him. Later, you can see me as a factory worker next to a Richard Gere lookalike walking out of the factory.

Let Me Do That

This was near the beginning of the music video era, and I noticed the production assistant was doing the sound. After the video, I asked him to let me handle the sound next time. After all, I had the time, the training, and the equipment.

A few weeks later, I got the call. For two nights, I shot the "Walk This Way" video (with Run DMC and Steven Tyler and Joe Perry) at the Capital Theater in New Jersey. It was my first gig running sound professionally for a music video. I spent two important days hanging out, making friends, and coming through with everything they needed. I became well known, first call for most projects coming to New York.

[Viewpoint: What's Your Professional Mindset?]

A daily selection of the top stories for AV integrators, resellers and consultants. Sign up below.

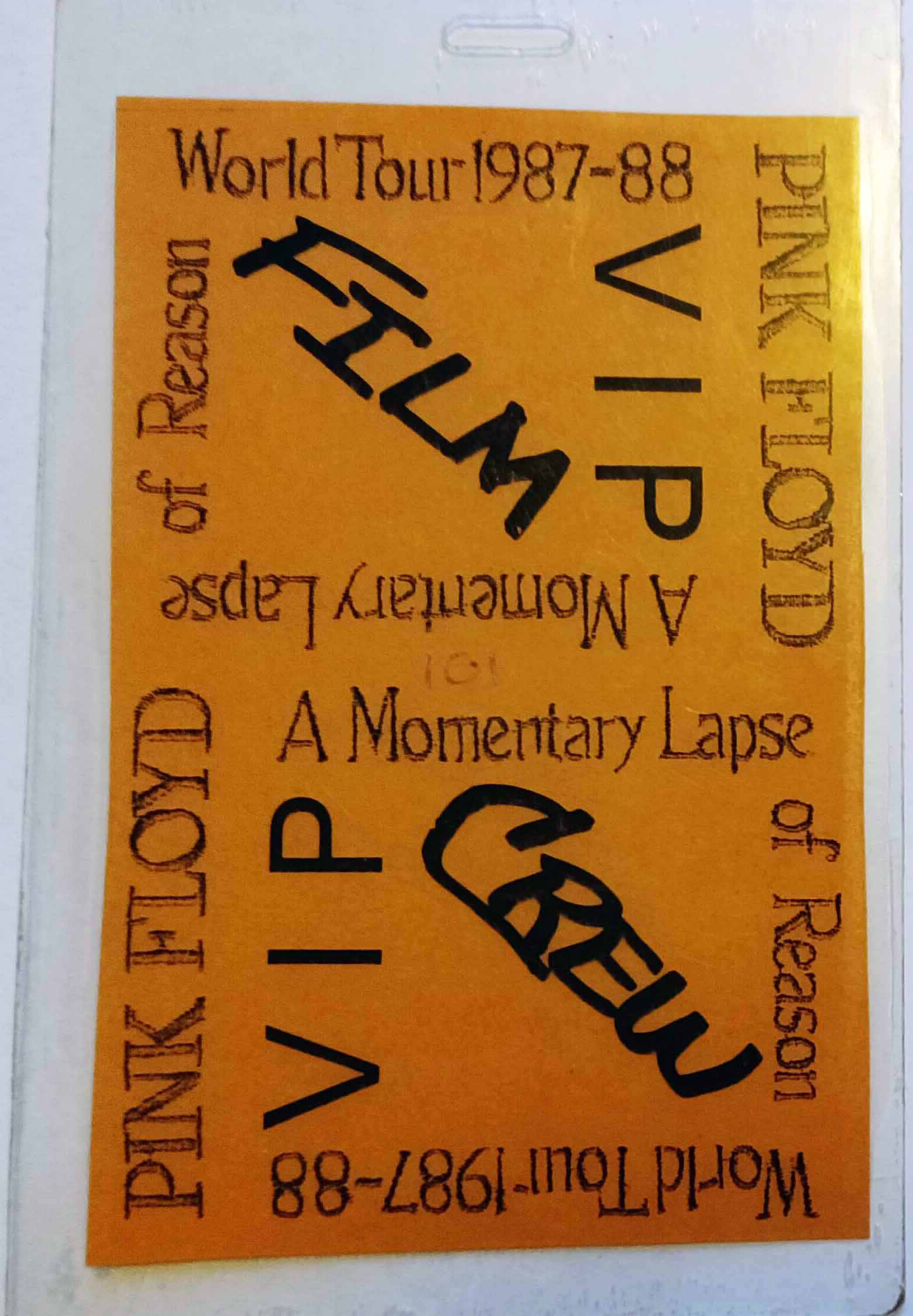

Fast-forward to August 1988. Pink Floyd was at New York's Nassau Coliseum for five nights, and they were filming a movie of their release and tour, A Momentary Lapse of Reason. I was actually planning to attend one of the shows.

A recording truck had been hired for the production. I had worked on some of these large multi-camera shoots, where I would have to run as much as two miles of cabling to hard wire communication, typically Clear-Com. In this case, they used Motorola walkie talkies for communication between the cameras and the director. There were 20 cameras at least, and the director needed to talk to each camera operator and tell them what to shoot.

On the early afternoon of the first show, I got a call from one of the production folks with whom I had previously worked. They did not get/could not get their headsets that worked with the Motorola walkie talkies. Think of what a helicopter pilot wears—big, double-muff headpiece with a noise cancelling mic. If I remember correctly, they would not be able to get them for a few days and needed me to provide them.

I owned some 36 of these radios, but I did not have the headsets. I was well connected, though, so I called everyone I knew, from film houses to sound guys to communication distributors, with no luck. (Remember, this was the 80s.) After a few hours, I checked in, and they still had not found anything. I told them not to worry—I would get something together and be there in a few hours.

Shot in the Dark

My mentor and friend, Bernie Zuch, and I discussed this. I rented a lot of equipment from him, including the walkies I owned. He said he did have single ear earpieces that would connect to the Motorola radios with an adapter. Of course, this would be useless—the concert would simply be too loud—but I figured there had to be a way to make this work (in the next two hours, mind you).

And then I got it. What they needed looked like shooting muffs, the double earmuffs you use at the gun range to protect your ears. There was a gun store nearby, so I called them. I bought 30 double earmuffs, and then I bought 30 earpieces from Bernie.

I got there in time and it worked. While not a perfect solution, this was a (video) shooting emergency. The director had to be able to direct the cameras; the production could do without having the camera operators talk back for the night. You can imagine the cost of a 60-person crew, rental equipment, etc., and the wasted money if they could not film that night.

[Beyond the Tech: Watch Your Language]

There was a combination of factors here that enabled me to accomplish this task. First and foremost was tenacity. Second was my years of experience in the audio/sound industry, and familiarity with all different types of equipment. Third was just my nature as an engineer, always looking to make something work.

When you're in the field, you learn to be clever. Whether you're using the right cable or even the right piece of gear for what you are doing is not as important as getting the job done. The show must go on, as they say.

There is a difference in this world between those who survive and those who thrive. When faced with an obstacle, what would you do? Say you just can’t do it, get someone else, or keep pressing until you find a solution? Let’s fill our industry with those who thrive—be tenacious and clever and know your trade. Here’s to your success!

I am Doug Kleeger, CTS-D, DMC-E/S, XTP-E, KCD, the founder of AudioVisual Consulting Services. I got into this industry frankly, not by choice, but because of my love of music. My first experiences were an AM radio and hoping my favorite songs would come on the radio. There were three standouts: Yesterday (1965), the Hawaii Five-0 theme (1968), and A Boy Named Sue (1969). I was eight when my grandfather bought me my first radio from Lafayette (now defunct electronics store). I still remember perusing the pages of their catalog, looking at all the different types of equipment, putting together systems in my head. Who knew? I still do that today…can you imagine…more than 55 years later!