Intercoms: A History of Distance

From analog to digital to the cloud, how have production crew communications evolved?

The earliest intercom uses date back to the late 1960s and early 1970s, when concerts became too loud to allow for waving pieces of paper or shouting from the stage to the back of the hall.

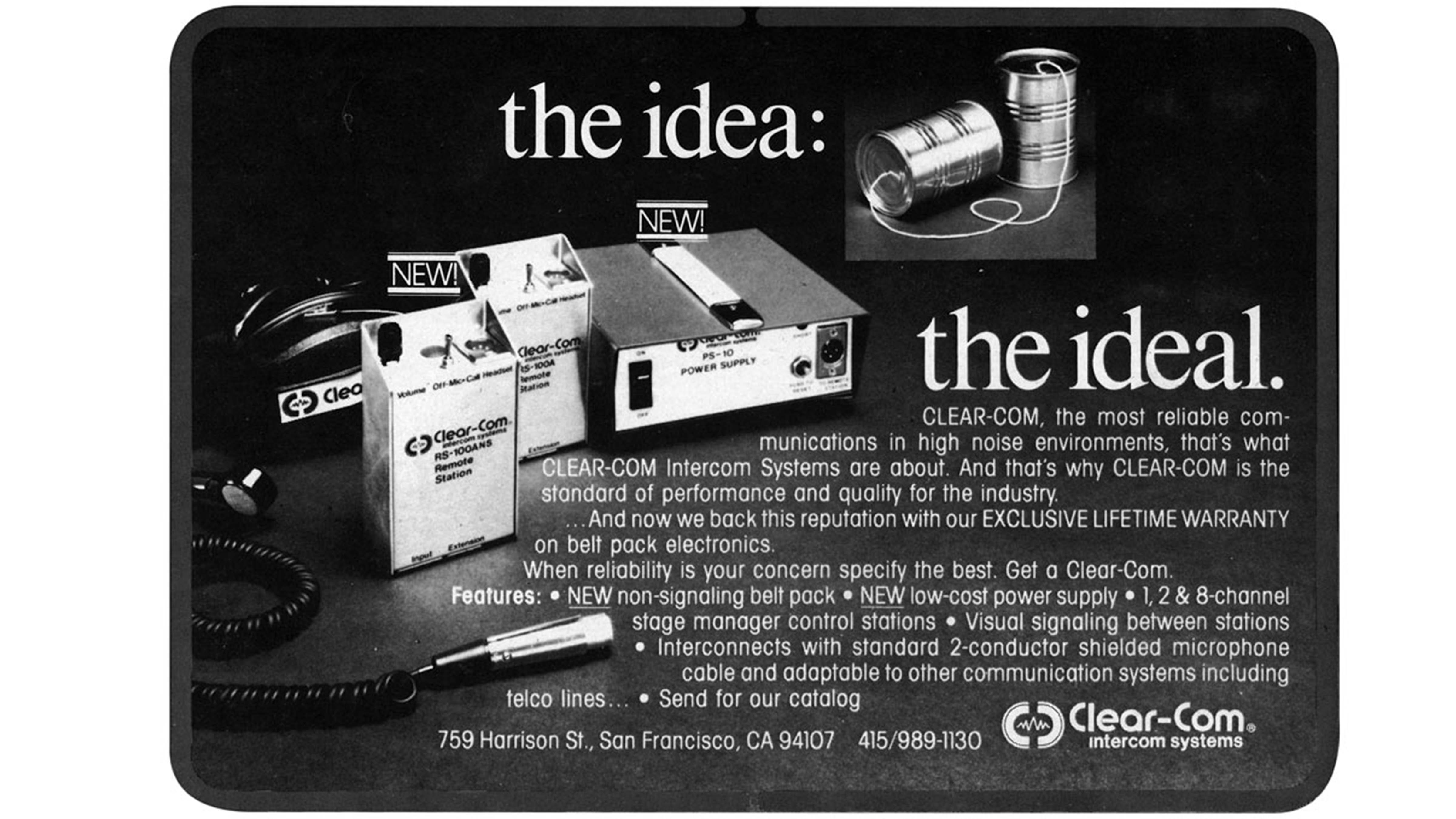

The brilliant idea that Charlie Butten came up with was to use the mic cables that went from the mixer at the back of the hall to the stage, and then layer an intercom system on top of those mic cables. It was early duplex communications. Butten went on to start Clear-Com and is still involved in the company’s development and engineering work to this day.

That workflow he developed became the de facto means of communications for live events. Soon, other industries began to take notice, especially broadcast TV, which was struggling with efficient communications among multiple people across a studio or newsroom. It was a matter of seeing a workflow in one environment and spinning it toward a new direction.

[Editorial: Lessons from the Fantasy Football Waiver Wire]

Since these first early uses, intercoms have become common in broadcast, education, corporate, healthcare, aerospace, defense, and any number of commercial applications requiring concise, controlled communications among multiple parties. From the original concept of solving a communications need has sprung analog, digital, and newer IP systems in a range of configurations: partyline systems, wired and wireless, matrix, beltpacks, headsets, and mobile app-based intercom options.

An Analog Foundation

The technologies Butten and others developed laid the foundations for the early analog partyline systems. Users each had a beltpack at one end, a wall box at the other end, and a power supply on the system, allowing everybody to communicate in a partyline operation.

We still see modern analog partylines around the world in small theaters and music event venues that may not have the resources or the inclination to move away from plug-and-play wired partyline systems with a two-way radio interface. It remains the mainstay of most live performance venues around the world, and many newer systems are backward compatible. You could likely buy a current analog beltpack to put on a power supply that's 50 years old, plug it in, and it would work just fine as part of a current and still relevant intercom system.

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

However, as live events grew more complicated with multiple stages and more complex production elements, a greater number of large teams needed to communicate with each other and with talent. This is where a partyline system begins to fall short, because it can't really handle more than four to six channels. In the early days, large, elaborate shows tried using analog partyline and had tremendous difficulty trying to do as much as they wanted to do. That started the migration to matrix and then to digital partylines.

Enter The Matrix

The first matrix-based systems were a hybrid solution acting as a central switch allowing crews to connect and manage different partylines, while also coordinating point-to-point with people in fixed positions on panels to bridge the communications between partylines. This provided a two-to-four-wire interface, so the system could be managed more carefully and with the flexibility needed by the multiple teams requiring communications.

Instead of a partyline, which is a large loop of audio that everybody bridges, matrix intercom was more like a crosspoint routing switcher, and early on there were several people designing similar foundational ideas. Clear-Com's efforts were derived from a Canadian manufacturer, McCurdy, as well as U.K.-based Drake Electronics, with its broadcast four-wire matrix solutions. The Telex RTS version of the matrix intercom in the United States and by Riedel in Germany also contributed to matrix technology, increasingly being recognized as an appropriate solution for broadcast operations (and eventually other applications).

The advent of the digital matrix in the late 1990s made it much easier for people to employ a smaller rack-mounted kit connected in a more intelligent way to allow for the much larger productions, which were becoming the norm. The next big step addressed the need for more mobility, since teams were no longer only sitting in front of an audio mixer or video switcher. Some people wanted to be on the studio floor or be able to move between sites. Analog wireless gave them that mobility with duplex connectivity.

Instead of a partyline, which is a large loop of audio that everybody bridges, matrix intercom was more like a crosspoint routing switcher.

Companies like Vega and HME must be recognized among the developers of the early wireless intercom systems. Their idea was to take a partyline system—four or six beltpacks—and put them on either a one or a two-channel system so they could “talk” to each other. That ended up being an important direction that subsequently led to the development of other downstream intercom wireless innovations—and eventually to the wireless systems of today. From their efforts, others also got into wireless intercom, leading to the “classic” UHF-based wireless intercoms.

Digital Partylines

Of course, analog wireless was and always will be subject to interference. Early systems needed to be managed using the bands of frequencies allowable for use, and it required full-time teams of people on site to coordinate all the wireless feeds and make sure licenses were all secured, since analog wireless in the VHF and UHF band was subject to those kinds of restrictions.

[Viewpoint: How Fast is the Pace of Technological Progress?]

Around the year 2000, digital wireless added the ability to use license-free bands, such as Digital Enhanced Cordless Telecommunications (DECT) bands in Europe and equivalent bands in the United States. DECT auto band selection eliminated the need for such high levels of frequency coordination. The systems were automated and moved dynamically between the beltpack user and the receiver to mitigate any interference.

Today, interference may still be an issue in high-capacity areas where you need every drop of bandwidth, but it's not an issue for somebody to manually manage. It's simply a matter of co-sharing the available band.

Then there’s the development of wireless systems with zoned intercoms based on point-to-point capability. These initially were attached to matrix intercoms and then subsequently became their own systems operated individually. That move toward digital wireless intercom paved the way forward for what are now digital wired solutions, like Clear-Com’s HelixNet system, which basically takes the idea of a partyline and moves it to a digital platform.

The individual cables that defined each analog partyline caried just one channel. Digital partyline can put many channels into one cable by digitizing and serializing the audio into duplex streams. Digital partylines also carry metadata that identifies each channel and allows for elaborate signaling.

New Intercom Applications

Intercom systems often are the management and interface point for the person talking to somebody on an IFB, whether that’s talent or a director. For example, the director is in front of an intercom panel with individual talk paths usually controlled by a single button that go to all the different people on IFB. And in some instances, maybe everyone on an IFB group channel as well, so the director can talk to many people at once. Usually in talking to them, the director either cuts the audio or ducks it going into their ear, so they can talk over whatever else the talent is hearing.

Especially since the pandemic, we are seeing new uses for intercom, mostly in instances where group discussions or close collaboration are no longer permitted. For example, in courthouses where they can’t have people whispering closely in each other's ears, people are using discreet, wired, and wireless communications with headsets, particularly attorneys and their clients.

Other examples include testing aircraft designs, where people may not be able to see each other, but still need to communicate, flick the right switches, and test the right lines. In nuclear power plant decommissioning, people are working in large bodysuits, and they need a push-to-talk method for communicating with each other. Healthcare professionals often deploy wireless intercom for hands-free operations, including in teaching applications. There are also a myriad of other potential applications, from aerospace to corporate communications to transportation and manufacturing and more.

The Next Level

The current evolution that we're in now has moved intercom to IP, as digital platforms evolved into sending signals over standard networks, which would first be a local area network and then a wide area network—and then over the public internet.

[Cloud Power: What You Need to Know About Security in the Cloud]

With the development of new IP audio interface boxes, users can connect older analog systems over IP networks, effectively upgrading existing analog partyline systems that may have been in a theater for 20 years. Maybe they’ve identified a need to be able to connect to a rehearsal space in another building, and the only feasible way to get a signal there is over the internet.

There are so many more potential uses for intercom development as users continually discover new requirements for enhancing voice communications. One interesting topic is the cloud. Intercom companies at this point typically don't have a significant cloud presence, since low-latency duplex audio mixing and routing across many channels in a virtual system is quite a new technology.

There are other issues surrounding latency or scalability, but those will be addressed and resolved over time, and intercom surely will be cloud-based. Moving to the cloud will also help usher in the era of “intercom-as-a-service,” giving users the ability to “spin up or spin down” the capacity and capabilities needed for a specific time frame.

Ultimately, there's no one answer to the question, “Which intercom is right for me?” That’s been the one constant since those early days of communicating at a rock concert or in a TV studio. Many customers commonly use more than one type of system on a production or event, combining digital and analog, as well as wired and wireless workflows, with solutions from the various eras. A 50-year-old partyline beltpack will be sitting on an IP-based or cloud virtual intercom in the near future.

Simon Browne is the vice president of product management for Clear-Com.