Interactive Museum Tech is No Longer a Novelty

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

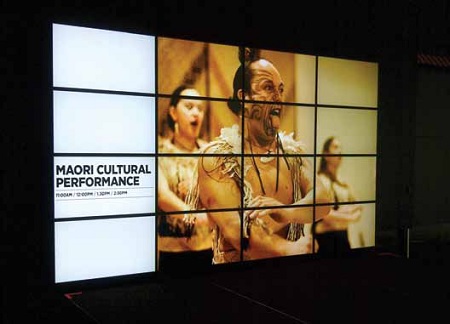

The Auckland Museum in New Zealand recently installed a striking 12x7-foot, 4x4 video wall in its entrance. It used to be that museums would have one high-tech draw: visitors would be able to interact with a specific exhibit, and most times, this involved AV.

With the proliferation of smartphones and tablets, and the synchronicity that goes along with, the average museum-goer is so accustomed to interactivity that it is inevitable; it’s becoming an expectation that museums of every shape and form are interactive, too. Where museum AV once meant a video display and the associated playback systems, now it means pretty much everything within—and even outside—an exhibition gallery’s walls. Add to that the question of museums and galleries moving audio and video data onto networks, and in AVB-capable systems.

“We see audiovisual moving into all the other technologies, not just ‘I’m going to hear a sound, I’m going to see a picture,’” said David Silberstein, director of commercial marketing at Crestron in Rockleigh, N.J. “Everything else that’s associated with that experience in the environment becomes part of that solution, and it needs to be managed and controlled and brought together and operated as one.”

Robert Badenoch, senior associate at AV design firm Shen Milsom & Wilke in New York, N.Y. notes that exhibitions are increasingly interactive with the incorporation of Internet connectivity. He points to artist Sabrina Raaf’s “Translator II: Grower,” an installation that features a robot that hugs the periphery of the gallery as it draws blades of grass on the walls. The grass blades represent how much carbon dioxide is currently in the air (depending on the number of visitors in the room), making the argument that grass needs CO2 to grow. But the installation isn’t just “local:” via the Internet, it also collects data from around the world to determine CO2 levels across the globe.

Jay Nichols, manager of the AV Division at CRC Technologies, at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art in Washington State. This museum relies on a Crestron DM transmitter, Lectrosonics SPNDNT Dante-capable DSP mixer / processor, two Lectrosonics DNTBOB 88 breakout boxes, and the Lectrosonics ASPEN SPN2412 24-input audio processor. For Badenoch, this means that as more and more installations require Internet connectivity, they will require the PCs, Macs, servers and so on to make it all happen. “And then there is the whole crop of issues surrounding display and sound, and getting it so that patrons can actually interact with these exhibits in a fluid way, in a way that meets the artist’s wishes,” he said. Museum design must now anticipate the need for this type of functionality— and sometimes functionality that isn’t always easy to predict, he adds.

Badenoch elaborates on this theme by citing a client that is continually exploring how to optimize technology to boost this kind of connectivity, interlinking its museum and educational spaces, performing arts facility and administration department and, in part, broadcasting to the public through its own radio station. “You’re looking at [various works] and then there are modern performance pieces, and it’s being broadcast live in audio or video, and then recorded so that it forms part of their online presence when you click through their media selections.”

Unique applications

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for tech managers. Sign up below.

On site, facilities are exploring how they can engage visitors from the minute they step through the doors. The Auckland Museum in New Zealand recently addressed this with the installation of a 12x7-foot, 4x4 video wall in its entrance. The 16 monitors are supported by two Matrox M9188 PCI Express x16 octal-monitor graphic cards.

“Museums are constantly looking for ways to enhance the overall visitor experience, and dynamic multi-screen installations are an effective tool,” said Caroline Injoyan, business development manager at Matrox Graphics in Quebec. “Multi-display platforms have become a bridge between today’s technology and yesterday’s treasures that keep guests actively engaged, informed and coming back for more.”

But museum AV isn’t just outward-facing; because multiple systems such as AV, lighting, HVAC and even turnstiles can be interconnected, facilities can now take advantage of what technology has to offer to optimize things like energy consumption. “There are times when a museum is open, but there just aren’t a lot of people coming through,” Silberstein illustrated. “The building has to respond to that.” When the lighting, heating and cooling systems are operating as one––along with the turnstile systems, which tell the staff how many visitors are currently passing through the space, it can. After all, why would you want to overheat or over-light a space where no one is present?

Silberstein notes that the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, NY, is a good example of how museums can take advantage of networked technologies. (Shen Milsom & Wilke designed the AV systems for this space.) The facility recently underwent a considerable technological facelift, with the incorporation of integrated AV and lighting featuring a number of Crestron systems, including control. An abundance of windows enables the facility to take advantage of daylighting, however the blind systems can follow the sun.

“The last thing we want is the sun to hit any piece of the works that are hanging on the wall, or wherever they are mounted,” he said. “It’s easy for us to say: on Tuesday, the sun is going to be in this spot [at this time], but on Wednesday, it’s going to be in the same spot two minutes earlier.” As soon as the displayed works are in danger of being exposed to sunlight, the blinds are programmed to automatically close.

No Operator Required?

At Bainbridge Island Museum of Art in Washington, a recent AV overhaul focused largely on accommodating a facility where operators are scarce. The upgrade resulted in the integration of a Dante-capable Lectrosonics SPNDNT DSP mixer/processor and two DNTBOB 88 breakout boxes to increase the capabilities of the ASPEN SPN2412 24-input audio processor that was already installed in the museum. This latter component is used to mix microphones and line-level sources from three stage floor boxes in the facility’s auditorium, as well as wireless mics and pre-amp signals from the surround sound processor. The upgrade expanded the system to include museum-wide paging for emergency announcements, and the SPNDNT handles mixing from sources throughout the museum’s 16 audio zones. What’s notable about these systems is that they enable the museum to manage the audio without necessarily requiring someone to run the soundboard.

“This is an installation where there is no operator on hand, and things have become much easier in terms of operator-free environments,” said Karl Winkler, director of business development at Lectrosonics. The systems can be programmed to cover certain zones at specific times of the day, and they now feature conditional language––if/then statements: if the another part of the system’s status is X, then this part of the system won’t override it. “With thorough programming, you don’t need an operator, and yet you can have very sophisticated automation happening with very simple controls.”

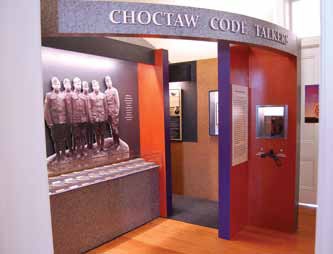

The Choctaw Code Talkers exhibit in OK uses Alcorn McBride technology. The Bigger Picture

While museums are becoming increasingly technological, technology isn’t necessarily the main focus. “It’s not about the technology leading these decisions; it’s about a consensus upon what the visitor experience should be, which then dictates display signage and audio, and pervasive network connectivity throughout all of the facility,” Badenoch said. “It happens in support of the bigger picture. Visitor experience is the institution, the branding of the museum and the kinds of exhibits that are hosted, the curation of those exhibits and the ongoing changes that they expect. These are very much not technical issues. These are really museum-planning issues.”

Carolyn Heinze is a freelance writer/ editor.

info

Crestron

www.crestron.com

Lectrosonics

www.lectrosonics.com

Matrox

www.matrox.com

Shen Milsom & Wilke

www.smwllc.com

Museum AV in Action at the Parrish

The Parrish Museum, founded in 1898, is the oldest and largest museum serving the Hamptons with arguably the most high-tech AV in the area. Because the Parrish, founded in 1898, is the oldest and largest museum serving the Hamptons, trustees took their time to build something truly special. Their efforts have resulted in a striking new building by Pritzker Prize-winning architects Herzog & de Meuron, set on 14 acres of meadow in Water Mill, New York. The technology inside is striking as well. Given the demands on the lighting and AV controls and on video distribution, integrator Bri-Tech, Inc. based these systems on technology from Crestron.

“The requirements in the Parrish Museum are much more demanding than in any home or commercial structure,” explains Brian McAulff, Bri-Tech president. In addition to rigorous control of temperature and humidity, lighting levels must be controlled as well to avoid damage to the artwork. Although the architects included skylights to provide each gallery with soft, natural light, they planned their size and placement carefully to limit lighting levels.

ARUP of New York, the lighting designer, supplemented the skylights with long lines of Nippo Seamlessline fluorescent fixtures, which electrify the tubes from behind, rather than at the ends, to allow smooth and continuous illumination without socket shadows. These fixtures are dimmed with Bartco Astara Universal PWM interfaces, which use digital pulse-width modulation to provide extremely consistent illumination across each tube and from fixture to fixture. The demands on the lighting controls are challenging, as well.

Local codes required the museum to provide an emergency lighting system, and the museum wanted to make sure it would operate within the same minimum and maximum limits to keep artwork as well as patrons safe.

McAulff says Bri-Tech engineers designed lighting controls using Crestron photo cells to read the lighting levels in each gallery, then signal a Crestron PAC2 processor and, through it, a series of Crestron GLX-DIM6 and GLX-DIMFLV8 dimming panels, which supply the voltage to each PWM interface. Curators can set maximums from the Apple iPad equipped with the Crestron app, or from a Crestron Cameo keypad. For the full project details, visit crestron.com.

Carolyn Heinze has covered everything from AV/IT and business to cowboys and cowgirls ... and the horses they love. She was the Paris contributing editor for the pan-European site Running in Heels, providing news and views on fashion, culture, and the arts for her column, “France in Your Pants.” She has also contributed critiques of foreign cinema and French politics for the politico-literary site, The New Vulgate.