Is Lecture Capture Good or Bad For Higher Education?

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Wainhouse analyst Alan Greenberg opines that “Lecture capture technology is quietly transforming how education is

delivered, ‘flipping’ the classroom.” Pictured above: Dr. Bob van den Brand records a lecture via Mediasite by Sonic Foundry at the Tilburg School of Economics and Management in the Netherlands.Although it seems hard to believe, almost 30 years ago the courts were deciding whether it should be legal to record video content for future playback. The now-famous “Betamax case,” originally filed in 1976, revolved around the issue of “time shifting,” the practice of recording television programming for viewing at a later time, at the discretion of the broadcaster.

In 1984, the Supreme Court decided that time shifting “has no demonstrable effect upon the potential market for, or the value of, the copyrighted work.” How wrong they were. Today, top rated TV sitcoms command as much as $5 million per episode in syndication fees. With the advent of the Internet and streaming technologies, the impact of time shifting is felt far beyond the broadcast industry, across all industries. But nowhere is the impact and potential greater than in higher education and corporate training.

Time shifting and the practice of recording video content for later playback on demand is at the core of the hottest technology in higher education and training: lecture capture. Lecture capture systems are a subset of streaming technology products, designed specifically for the capture and management of classroom content. Lecture capture has probably been practiced since long before it was officially named “lecture capture.” The term itself seems unfairly limiting; what distinguishes it today from the simple act of recording and playing back a class is the use of feedback mechanisms and the ability to annotate and mark sections for later review and comment.

There’s no question that lecture capture is increasingly popular among students and educators. Analyst firm Wainhouse Research conducts annual surveys on various forms of educational technology. Their 2011 “Distance Education and e-Learning Metrics Survey” report predicts that by 2016, lecture capture “is likely to be as pervasive as email on college campuses.” Among their findings, they noted that 75 percent of organizations currently deploying lecture capture intended to spend more or the same on the technology in 2012. Wainhouse analyst Alan Greenberg believes that lecture capture is likely to become a mainstream technology in higher education (even more than videoconferencing or virtual classrooms), primarily because it supports both distance and brickand- mortar learners. In 2010, their survey found that 71 percent of educators in higher ed were already using lecture capture and streaming technologies; that number increased to 77 percent in their 2011 survey, and only 5 percent had no plans to use these technologies.

The Tilburg School of Economics and Management uses Mediasite lecture capture to improve student engagement.“Lecture capture technology is quietly transforming how education is delivered, ‘flipping’ the classroom,” Greenberg said. “But there are many academics who hate it and won’t try it. And it works well in some hands, not so well in others.” He said that simply recording a classroom-delivered lecture may not translate well for online delivery. “I’ve seen various community colleges implementing this technology, and those with instructional designers do far better than those who do not have instructional designers— staff to help faculty transition content to an online context,” said Greenberg.

Despite all of the attention and optimistic predictions, lecture capture may not be appropriate for all types of institutions of higher education.

“I have found a lot of early adopters among graduate and professional programs, like MBA programs and colleges of medicine,” observed Greenberg. “It’s most likely to be used in educational environments that have a lot of technical things to show, like medical procedures or the data and charts that you’d see in business school environments.”

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for tech managers. Sign up below.

The Campus Computing Project, founded by Dr. Kenneth C. Green, has been studying the role of information technology in American higher education since 1990. In its 2011 Campus Computing Survey, they note that while 80 percent of respondents representing public and private universities agree that lecture capture is an important part of their plan for developing and delivering instructional content, actual depment is far lower than that statement would imply: deployment remains at about eight percent of classes taught in public and private universities. Among private fouryear colleges, less than four percent of classes include lecture capture and review capability.

Vaddio’s AutoTrak 2.0 is an HD camera tracking system with audio, Smooth Trak, and AutoTilt technology. Instructors wear

IR lanyard belt packs that emits infrared light received by an IR PTZ camera, so wherever they move, they will be “captured.”Like any potentially disruptive technology, lecture capture has its critics. Mark Smithers, an educational technologist with Melbourne, Australiabased Swinburne Online (a joint venture between Swinburne University of Technology and the online recruitment company Seek) has provocatively questioned whether it’s “the worst educational technology.” In a 2011 blog post, he cites four reasons why lecture capture might not be all its advocates claim:

1. It perpetuates an outdated and increasingly discredited passive learning experience (the classroom lecture).

2. The technology does not engage the student.

3. Traditional lectures aren’t designed for online delivery.

4. It diverts resources that could be better used in consolidating other enterprise-wide educational technologies, and staff development and support.

Since Smithers’ blog post last year, over 42 responders continue to debate and comment on his position. Most are in support of his basic premise: lecture capture technology isn’t inherently bad, but an over-reliance on this shiny bright new toy (to the exclusion of other elements in a “blended learning” approach) by educators and students is probably not in the best interest of real “learning.”

Perhaps the issue is less with the technology and more with the lecture itself—specifically, the content’s subject matter and how it is delivered.

Founded in 1984 as a series of live conferences, TED (which stands for Technology, Entertainment, Design) has transitioned to an online lecture series. Since 2006, more than 1,300 TED talks on a wide range of topics have been viewed over 500 million times online. Besides compelling content and engaging delivery, at least part of its popularity may be due to the fact that the average lecture lasts less than 15 minutes. Why 15 minutes? TED curator Chris Anderson has been quoted saying, “It’s turned out that that time length, while being long enough to say something substantive, is short enough to hold people’s attention, even on the internet.”

There is science to support Anderson’s observation. A 2010 study at the University of Bath in the U.K. on the use of lecture capture systems found that over a 12 month period, 5,364 hours of lecture capture content had been watched with 33,133 views, which averages out to about 9.7 minutes per view. Some observers attribute this short duration to the idea that students are conditioned to traditional television with its many commercial breaks. Others, like Dr. John Medina, director of the Brain Center for Applied Learning Research at Seattle Pacific University, claim that the typical natural attention span is about 10 minutes. Whether it’s the content or the duration, it’s enough to raise the question of whether listening to the playback of a live lecture can be as effective as actually attending the event in person.

One of the most common criticisms of lecture capture systems is that students will opt to miss class since they know it’s been captured for later viewing anyway. While this topic has been explored by various researchers, results are inconclusive. There’s no question that lecture capture is seen as an effective way to “catch up” on missed classes. A survey conducted in 2010 by Echo360 of 1,746 U.S. college students found that 95 percent of those who missed classes used lecture recordings to catch up. Whether it actually encourages skipping class has not been proven.

A study by technology vendor Tegrity surveyed 6,883 college-level students who had experience using their products in the fall of 2010. Eighty-five percent of respondents said that having access to recorded lectures made study somewhat or much more effective than normal, and almost three quarters (73 percent) indicated that lecture capture significantly or somewhat improved their grade in the course. Although about 20 percent indicated that it reduced how often they came to class, an even higher percentage (23 percent) felt that it actually increased how often they attended class.

The Silver Bullet?

A recent survey sponsored by Time magazine and the Carnegie Corporation of New York found that 89 percent of U.S. adults and 96 percent of senior administrators at colleges and universities said higher education is in crisis. To ponder the question, a day-long summit was held in October 2012 in New York City co-sponsored by the Carnegie Corporation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, drawing more than 100 college presidents and other experts. Among the problems they identified were the astronomical costs of quality education, low completion rates, and too little accountability. In discussion of potential solutions to these problems, attendees agreed that higher education must “innovate or die.” The discussion naturally led to how technology could foster innovation and help extend higher education beyond the campus. Andrew Ng, an associate professor at Stanford and co-founder of online education provider Coursera, said that, “for many students around the world, the choice is not between a MOOC and Stanford—it’s between a MOOC and nothing.” Since the heart of any online class is a lecture capture system, the future for this enabling technology indeed looks bright.

Mark R. Mayfield is an independent consultant, analyst, and writer in the communications technology industries. Reach him at mmayf56@hotmail.com.

Teaching Visual Learners

/ / / By Eric Vidal

An oft-quoted statistic says that 65 percent of students are visual learners. Among the smartphone/YouTube generation, the odds are that percentage is much higher.

The current generation of learners is used to being visually entertained on a constant basis, making the use of webcasting, video, and other rich content in the classroom critical if educators want to reach them more effectively, and at a deeper level.

One of the challenges of increasing the use of this type of content, however, is storing, managing and distributing it. Most school networks have only rudimentary capabilities in this area, making it difficult to deliver the information learners need in the format in which they’ll best receive it.

InterCall has one solution to the issue; the InterCall CorporateTube is an internal video content management solution developed in partnership with Kaltura. InterCall CorporateTube leverages Kaltura’s open source video technology to make it easier for educational institutions as well as corporate trainers to store, manage, and distribute all of their rich media content.

Part of that content is webcasting and virtual environments, two of InterCall’s core product offerings. By replacing traditional school assemblies in the gym or other large gatherings with webcasts, either on a central monitor in the classroom or individual student devices, educational institutions can minimize disruption in the school day while keeping viewing groups to a size teachers can control. Lessons can be made available on demand so learners can quickly search, find and consume content in a rich and engaging way.

A virtual environment allows students who are unable to attend school in person to participate. In one higher education setting, offering class via a virtual environment increased attendance on Fridays significantly, and increased the number of questions asked per class by 10 times.

Eric Vidal is the director of product marketing for the Event Services Business Segment at InterCall (www.intercall.com).

What’s missing from MOOCs?

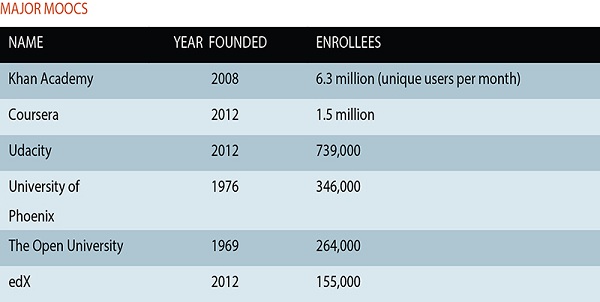

- A more recent extension of the lecture capture concept has been creating a stir in the higher education technology world. MOOCs, or Massive Open Online Courses, have been both praised and vilified by educational theorists, practitioners, and administrators. And, perhaps, with good reason on the side of both points of view.

A MOOC can be attended and accessed by anyone with an Internet connection— for free. The Bill Gates-endorsed “Khan Academy” can be considered a type of MOOC. High prestige institutions like Princeton, University of Virginia, University of Pennsylvania, Stanford, MIT, Harvard, and Georgetown (to name just a few) have also embraced the concept, as have hundreds of thousands of online students. Obviously, MOOCs have the potential to disrupt (or save) the business model of higher education. But many observers question the quality of the “education” they produce; while the numbers of enrollments are impressive, there is no way to tell to what degree an online student absorbs or synthesizes the lessons learned into any kind of innovative thinking. Is the value of an online MOOC credit the same as the value of a Harvard attended course? As one critic puts it, “The [online] delivery of course content is not the same as education.”

In October 2011, after 160,000 students signed up for his online course on artificial intelligence, Stanford professor Sebastian Thrun and several partners started their own MOOC company, Udacity.

What’s missing is the collaborative experience that can’t be replicated in massive multicast courses. According to renowned technology writer Nicholas Carr, skeptics argues that the essence of a college education lies in the subtle interplay between students and teachers that cannot be simulated by machines, no matter how sophisticated the programming.

While the enrollment numbers are impressive, if MOOCs are to succeed, what matters is the “graduation rate.” Of the 160,000 people who enrolled Thrun’s first Udacity class, only about 14 percent ended up completing it.

Spotlight: IP in Education

Georgia’s Walton County School District

Walton County School District, based in Monroe, Georgia, has always made educational innovation a top priority. Recently, the district was looking to transition from an outdated coaxbased video and audio communications system to an IP network-based solution that would enable it to cost-effectively stream live, video-on-demand (VOD), and multicast video feeds simultaneously to an unlimited number of classrooms.

REALISTIC BUDGET

Working with a limited budget, Walton County Schools set out to find a low-cost IP-centric streaming media solution with encoders capable of delivering high-quality SD video and audio signals to more than 15 schools district-wide. The district hired AV systems integrator Media Products, Inc. to help design the new streaming media portal, and together they conducted a thorough examination of technologies that fit the criteria. Ultimately, the district chose Visionary Solutions’ AVN200 and AVN210 encoders to power the new IP solution.

One of the major benefits of migrating to an IP-based video infrastructure that can stream video and audio content over local and wide area networks (LAN and WAN) is the flexibility to control a wide range of content, including student and faculty-produced videos as well as multimedia from leading broadcast and cable networks, from a central location. In doing so, Walton County Schools has been able to distribute live announcements in a much timelier manner. This dramatic increase in operational efficiencies has been critical in lowering their expenses.

The district uses Visionary Solutions’ AVN200 and AVN210 solutions to compress SD video and audio into MPEG-2 real-time streams that are viewed on projectors within the classroom. Visionary Solutions’ AVN encoders feature standard MPEG-2 hardware compression and optimized network interface technology capable of delivering full frame-rate video and CD quality audio.

USABILITY

Aside from ensuring video quality and centralized control, another major objective of the project was usability. School district media specialists can easily manage the AVN encoders via an intranet site that includes links to each encoder’s embedded Web server. The district’s internal website also includes links to VLC, a free and open source cross-platform multimedia player compatible with a wide range of multimedia files as well as DVD, audio CD, VCD, and streaming protocols, enabling teachers to instantly download a media player and stream high-quality video and audio content in the classroom.

info

Visionary Solutions

vsicam.com

Walton County Schools

walton.k12.ga.us

Enthusiasm for Video Outstrips School Capabilities

The media production team at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington, was a victim of its own success. The team had begun a modest program to stream video of important university events. The videos proved to be extremely popular and the team had increased the number of UNCW events covered, including graduations, convocations, press conferences and other events. It was clear to Chip Bobbert, producer and director in the Department of Media Production, UNCW, that using Adobe free software and inexpensive video capture cards was no longer an adequate solution.

At UNCW, approximately 13,000 undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral students experience a unique blend of teaching, research, and service learning opportunities. “We were delighted that so many students, parents, alumni and friends of UNCW utilized the video we offered to keep up on school events, but the amount of video we were streaming and the number of people viewing it was outpacing our capabilities,” Bobbert noted. “We knew we had to move to the next level of sophistication in our video hardware and software to ensure we maintained the quality in our video solutions that reflects the quality of the institution we represent.”

Bobbert and his team met to discuss solutions and decided there was no room for failure or less than perfect video quality. After researching product lines, Bobbert chose ViewCast’s Niagara 9100 Streaming HD Video Encoders. The encoders now form the cornerstone of UNCW’s streaming media upgrade, delivering multiple, simultaneous streams in a variety of formats and is optimized for live streaming/ simulcasting, webcasting, and archiving/video on demand. It can be configured for a variety of video and audio inputs, including HD-SDI, component Y/C, and composite video with balanced, unbalanced, embedded and AES/EBU audio. A flexible Web interface enables remote setup, control, and monitoring, as well as access to all popular industry streaming formats.

UNCW plans to increase the number of events covered by video streaming from 12-15 per year to more than 20 per year. Bobbert’s team is exploring making video available 24/7, something impossible before the upgrade. The team is also looking at adaptive streaming.

“We are eager to have our expansion plans underway. It’s something we had in mind for some time, but until we were comfortable that our video infrastructure was able to handle more content and always-on availability, we were not willing to expand,” Bobbert said. “We also know that friends of the school will view video on smart phones, tablets, and other devices as well as computers; we’re now able to provide a quality experience for everyone.”

info

University of North Carolina Wilmington

uncw.edu

ViewCast

viewcast.com