The ROI of Everything— How to Make Better Decisions

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Time Is Money, But You Still Have To Prove It.

It’s Rental & Staging Roadshow season once again and we’re talking about making better decisions. One of the best tools I have found for this is to calculate the Return on Investment (ROI) of a potential decision and let the numbers help you make your mind up. Some applications of ROI are simple: a good client wants to rent a camera every month—it makes sense for you buy it rather than cross-rent. The complicated part of calculating ROI is how to value personnel time used for intangible work. To find the answer, you have to know what your personnel would do with more time if it were available.

When to Hire More Help

Consider the time used in developing a proposal. In rentalthink, the event proposal is simply a long, detailed rental budget. At some companies, a budget is not complete until all cabling, accessories, labor scheduling, logistics, and sub-rentals are reconciled to estimate gross profit. In terms of personnel time, it can take 2-3 times more man-hours to generate a proposal this way and for only marginally better planning (on something that may or may not even confirm). Even in companies where the proposal process is more fluid, generating proposals for projects, which the firm has little or no chance of winning, often consumes 25 percent or more of sales and sales support time.

Let’s say you have several options to shrink this process and one of them is to eliminate checking for equipment availability for projects more than six weeks out. The naysayers’ the response comes back in terms of dollars, “What if we sell something we’ll be out of and have to sub-rent?” The counter-response should be “What is the value of the time applied to writing proposals in terms of lost revenue versus an unplanned sub-rental?” Let’s do the math. If a salesperson generates $100 thousand in new business per year by spending 200 hours (10 percent of their time) calling potential customers, and changing the proposal process will free up another 200 hours, what is the potential ROI of the change? Let’s split the timesaving and devote 100 hours to better customer service and 100 hours to business development. This could be worth another $100 thousand in new business (what’s the value of the retained business?). Multiply that potential growth across all sales folks and the ROI suddenly becomes HUGE. Checking availability is only one way in which stagers over-produce proposals. What about line item’ing system components or entering in a complete crew schedule? How much time does that add?

Match the Work to the Worker

Managers tend to think that all sales time is free and all technician time must be billed. When outsiders look at our industry they are surprised at how little our sales folks know about sales and how much we rely on them for technical knowledge. Forward-thinking stagers often choose to dedicate a technical resource (engineer, project manager, lead technician) to a sales support role. I don’t mean a part-time, take a phone call during load-in, and crank out a drawing in your hotel room scenario. I mean chain-a-person-to-a-cubicleand- bring-them-sandwiches-they-aretoo- valuable-to-let-out-of-the-office solution. Having someone to assist sales in making good choices, scrub confirmed orders, solve technical dilemmas, and be on hand to reassure the customer that “yes, the sales person is correct, that will work” has an ROI.

Let’s do an example. Let’s say this sales support person is paid $50 thousand per year including all benefits etc… If their assistance will reduce the time a salesperson spends on proposals from 1200 hours per year to 800. What can a salesperson do with 400 more hours? (Suppress smart-alecky remark here). In this example let’s use the time to handle more existing business. If you have five sales people, you could now accomplish about the same amount of work with only four. On top of all this, the sales support person will reduce mistakes, find more cost-effective solutions, and probably use internal resources more efficiently than a salesperson – more ROI to calculate.

Buy New Gear

The real benefit to calculating ROI is to drive timely decision-making. Putting a value on a change (and capturing all the side-benefits in terms of dollars) can help make the discussion more productive. Here’s another typical example: You need to replace an aging f leet of conference projectors. The arguments are qualitative: they look old, competitors are renting better projectors at the same price, when we sub-rent the replacements are nicer than ours, and we send two units in case one fails, etc… The counter-arguments are quantitative: they are paid for so we should use them as along as possible; we can’t sell them for anything so why not keep them around; new projectors will increase our depreciation expense and reduce our net profit.

A daily selection of the top stories for AV integrators, resellers and consultants. Sign up below.

To make the case for buying new gear, the easy part is estimating the ongoing cost of maintenance and sub-rentals. But there are other issues to consider: Do the old projectors take longer to setup? Are there more service callbacks once they are setup? What is the cost of each extra trip you make to the room/venue/location when the customer isn’t happy? What other work-arounds have you institutionalized on account of these units? This is a more complex example because you also have to factor in the negative effect renting old projectors to your customers. Do they hurt your brand? Do they diminish the value of other equipment and drive your price points down? If you can point to one customer that was driven off by these old units (or other old gear), what is the net value of their business?

In the end, ROI calculations generally confirm what you already know, but were afraid to face. And once you know the value of the necessary decision, the clock starts ticking. Every day you postpone your choice will cost you in lost time/profit. Remember, sometimes the ROI isn’t enough to justify the risk – but until you calculate that ROI - you simply won’t know. These are just a few ways you can apply ROI to complex processes. Once you get started you will find so many more.

Tom (T.R.) Stimson, MBA, CTS, is president of The Stimson Group, a Dallas-based management consulting firm providing strategic planning, market research, and profit-through-process services to the Audiovisual Industry. Tom is the 2010 President of InfoComm International, a member of the ETCP Certification Council, and keynote speaker for the Rental & Staging Roadshow. Contact him at tom@trstimson.com

Reminding Us That Recessions are Game-Changers

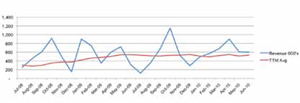

XYZ Company Revenue Jul ’08 - Jun ’10

The good news this summer is that most of the companies I speak with are seeing higher revenues. July and August have been unusually busy in what has traditionally been a slow period these past several years. The nature of events still seems to be budget-conscious, but there is a trend towards innovative applications of practical technology. It all sounds like good news in the short term, but let’s pull back and take in the perspective.

When slow months become busy it could mean that busy months will become even busier. Indeed, stagers are reporting bigger than normal pipelines for October 2010, which seems a good indicator that the year will finish strong. But in this industry, months are not good indicators – especially coming out of a Recession. The lesson is to not necessarily view a busy July as a windfall. It could be the new busy, and the old busy will be redistributed across other months.

So will 2010 finish strong for you or not? To make an educated guess, take a look at your trailing 12 months average revenue for the past two years. (For every month, total the previous year’s revenue and divide by 12. You will need three years of data.) In my sample chart, you can see that this company has had huge monthly ups and downs but their AVERAGE is actually kind of flat this year. They might expect their year to to trend up, but as you can see – not dramatically. This probably means that great October will be offset by slow months.

Try plugging your revenue forecast into your chart. Is there a dramatic uptick? It could mean that your forecast is too optimistic. What else could affect the resulting trend? Well, the economy could introduce gigantic variables, but that’s another topic for another day.