Controlled Chaos

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for AV/IT professionals. Sign up below.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

An AV Contractor Meets Several Thousand Feet of Analog Audio Cable.

Some years ago, the school of music, of which I am a part, sold our remaining large-format analog recording console and analog multi-track tape recorder in an effort to provide our students some hands-on time with newer digital equipment they would likely encounter in the field. We replaced this with Pro Tools software, along with one of the company’s then-current large format mixers. The mixer is actually a very expensive mouse, since the only audio that passes through it is located in the center section of the mixer, where it is directed to the loudspeakers for monitoring.

While the controller was nice, it did not lend itself to teaching simple concepts like signal flow and gain structure; we all pined for another analog board in the control room. When it was announced that we were converting an adjacent space specifically for use as a scoring stage, the fix was in: the digital controller would be out, and a current model analog mixing console was coming in. A top-of the- line board deserves a similarly qualified room, so the control room was also in for an industrial-grade makeover, with upgrades for acoustics, new speakers, and the signal path. The department chair hired a well-known technician whose specialty is the installation and commissioning of large-format analog mixing consoles for major recording studios worldwide. Both he and the chair had worked together before, and they looked forward to a summer collaboration on the project.

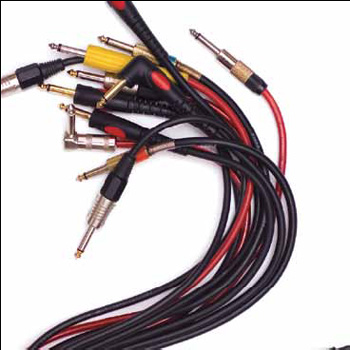

The grand plan included the installation of new tie-lines from the control room into the newly-constructed scoring stage so that students could experience a genuine film scoring session on campus. This meant running multiple analog audio cables for a couple hundred feet between the two buildings. That’s where things began to go sideways.

For starters, the cable is dear; twisted- pair copper balanced analog audio wire sans plenum, priced at about $9 a foot in small quantities, with an OD of somewhat less than 1/8-inch. The console has 80 individual inputs, and is capable of many more sends and returns. We estimated 96 tie-lines would serve between the two buildings, taking advantage of a sixinch conduit installed for this purpose. A cover in the concrete between the structures should allow for an easier pull from the mic panels in the scoring stage to the control room’s 96-point patch bay, where EDAC multipin connectors would connect it to the console.

On the other hand

The fait accompli bid that went out included the wire and the pull, plus setup and connections into the mic panels in the scoring stage and into the machine room, where the wire snake would be fitted with EDACs and joined to the console and patch bay. The vendor who won the bid was an AV system integrator and contractor who shall remain nameless, but they are an approved vendor and probably do quite well with AV and IT in the classroom; maybe they’re specialists in digital telepresence, I don’t know. But it soon became clear that recording studio installations were not among their strong suits.

A daily selection of features, industry news, and analysis for tech managers. Sign up below.

Where the console tech had cut a couple of modest circular holes in the drywall between parts of the machine room, the AV integrator, having decided that there wasn’t enough hole for all the wire, evidently took a Sawzall and made the small holes into a large, jagged rectangles. In the end, the wire was pulled, although some miscalculations with the winch make me wonder about the integrity of the wire in the end. Other concerns regard the conduit used, which appeared not to have seen wire in some time judging from the condition of the likely non-weatherproof caps. How long before a heavy rain fills the conduit with water? The EDAC connectors were in the end assembled by the console tech, so they should be perfect. The mess in the machine room was cleaned and organized also by the console tech with some help from faculty volunteers. However, it is quite possible that some of the tie-lines between buildings will go south at some point, probably long after the remainder of the bid has been paid and the case is closed. The engineer will sit and wonder to where the second violins vanished, at least until he or she figures out that they’re missing.

Steve Cunningham is an assistant professor of practice at USC’s Thorton School of Music.